After scan through the article, I believe it's worthy posting a chapter ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS: Military Power of the Peoples Republic of China 2008, for everyone to have a glimpse of what US perceives Chinese military forces.

For the whole report, see http://www.defenselink.mil/pubs/pdfs/China_Military_Report_08.pdf

ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS

Military Power of the Peoples Republic of China 2008

Chapter Four

Force Modernization Goals and Trends

China pursues a three-step development strategy in modernizing its national defense . . . . The first step is to lay a solid foundation by 2010, the second is to make major progress around 2020, and the third is to basically reach the strategic goal of building informatized armed forces and being capable of winning informatized wars by the mid-21st century.

Chinas National Defense in 2006

Overview

Chinas leaders have stated their intentions and allocated resources to pursue broad-based military transformation that encompasses force-wide professionalization; improved training; more robust, realistic joint exercises; and, accelerated acquisition and development of modern conventional and nuclear weapons. Chinas military appears focused on assuring the capability to prevent Taiwan independence and, if Beijing were to decide to adopt such an approach, to compel the island to negotiate a settlement on Beijings terms. At the same time, China is laying the foundation for a force able to accomplish broader regional and global objectives.

The U.S. Intelligence Community estimates China will take until the end of this decade or longer to produce a modern force capable of defeating a moderate-size adversary. China will not be able to project and sustain small military units far beyond China before 2015, and will not be able to project and sustain large forces in combat operations far from China until well into the following decade. In building its forces, Chinas leaders stress asymmetric strategies to leverage Chinas advantages while exploiting the perceived vulnerabilities of potential opponents using so-called assassins mace programs (e.g., counterspace and cyberwarfare programs). The PLA hopes eventually to fuse service-level capabilities with an integrated network for C4ISR, a new command structure, and a joint logistics system. However, it continues to face deficiencies in inter-service cooperation and actual experience in joint exercises and combat operations.

Potential for Miscalculation

As PLA modernization progresses, three misperceptions could lead to miscalculation or crisis. First, other countries could underestimate the extent to which PLA forces have improved. Second, Chinas leaders could overestimate the proficiency of their forces by assuming new systems are fully operational, adeptly operated, adequately maintained, and well integrated with existing or other new capabilities. Third, Chinas leaders may underestimate the effects of their decisions on the security perceptions and responses of other regional actors.

Emerging Anti-Access/Area Denial Capabilities

As part of its planning for a Taiwan contingency, China is prioritizing measures to deter or counter third-party intervention in any future cross-Strait crisis. Chinas approach to dealing with this challenge centers on what DoDs 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review refers to as disruptive capabilities: forces and operational concepts aimed at deterring or denying the entry of enemy forces into a theater of operations (anti-access), and limited duration denial of enemy freedom of action in a theater of operations (area denial). In this context, the PLA appears engaged in a sustained effort to develop the capability to interdict or attack, at long ranges, military forces particularly air or maritime forces that might deploy or operate within the western Pacific. Increasingly, Chinas anti-access/area denial forces overlap, providing multiple layers of offensive systems, utilizing the sea, air, space, and cyber-space.

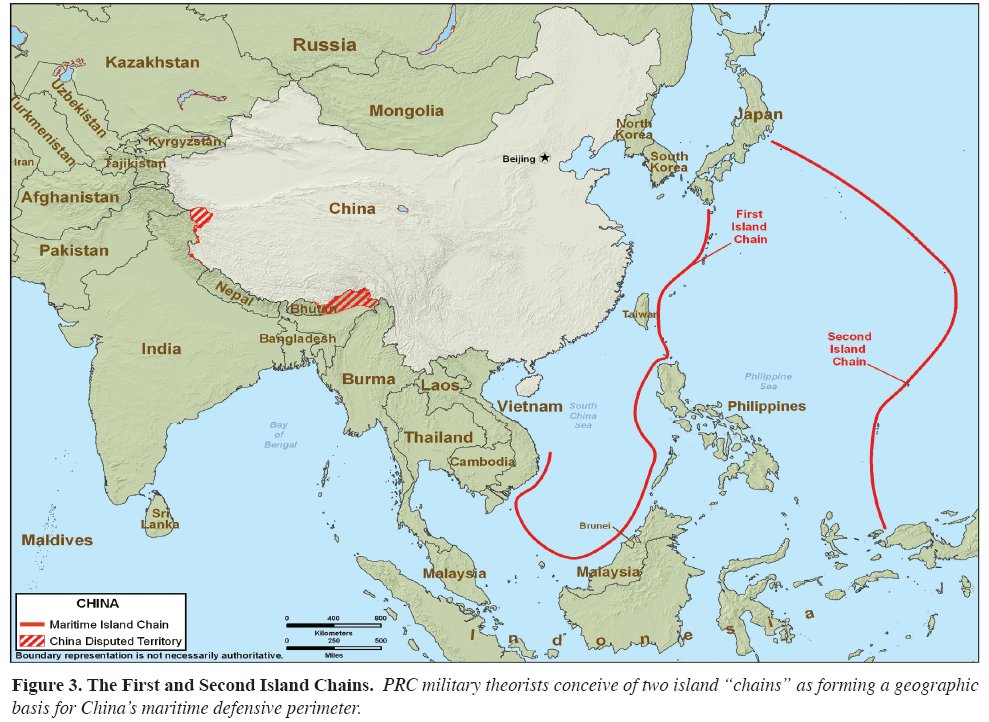

PLA planners are focused on targeting surface ships at long ranges from Chinas shores. Analyses of current and projected force structure improvements suggest that China is seeking the capacity to hold surface ships at risk through a layered capability reaching out to the second island chain (i.e., the islands extending south and east from Japan, to and beyond Guam in the western Pacific Ocean). One area of investment involves combining conventionally-armed ASBMs based on the CSS-5 (DF-21) airframe, C4ISR for geo-location and tracking of targets, and onboard guidance systems for terminal homing to strike surface ships on the high seas or their onshore support infrastructure. This capability would have particular significance, as it would provide China with preemptive and coercive options in a regional crisis.

PRC military analysts have also concluded that logistics and mobilization are potential vulnerabilities in modern warfare, given the requirements for precision in coordinating transportation, communications, and logistics networks. To threaten regional bases and logistics points, China could employ SRBM/MRBMs, land-attack cruise missiles, special operations forces, and computer network attack (CNA). Strike aircraft, when enabled by aerial refueling, could engage distant targets using air-launched cruise missiles equipped with a variety of terminal-homing warheads.

Chinas emerging local sea denial capabilities mines, submarines, maritime strike aircraft, and modern surface combatants equipped with advanced ASCMs provide a supporting layer of defense for its long-range anti-access systems. Acquisition and development of the KILO, SONG, SHANG, and YUAN-class submarines illustrates the importance the PLA places on undersea warfare for sea denial. In the past ten years, China has deployed ten new classes of ships. The purchase of SOVREMENNYY II-class DDGs and indigenous production of the LUYANG I/ LUYANG II DDGs equipped with long-range ASCM and SAM systems, for example, demonstrate a continuing emphasis on improving anti-surface warfare, combined with mobile, widearea air control.

The air and air defense component of anti-access/ area-denial includes SAMs such as the HQ-9, SA-10, SA-20 (which has a reported limited ballistic and cruise missile defense capability), and the extended-range SA-20 PMU2. Beijing will also use Russian-built and domestic fourth-generation aircraft (e.g., Su-27 and Su-30 variants, and the indigenous F-10 multirole fighter). The PLA Navy would employ Russian Su-30MK2 fighters, armed with AS-17/Kh-31A anti-ship missiles. Acquisition of an air refueling platform like the Russian IL-78 would extend operational ranges for PLAAF and PLA Navy strike aircraft armed with precision munitions, thereby increasing the threat to surface and air forces, bases, and logistics nodes distant from Chinas coast. Additionally, acquisition and development of longer-range unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs), including the Israeli HARPY, expands Chinas options for long-range reconnaissance and strike.

A final element of an emerging area denial/anti access strategy includes the electromagnetic and information spheres. PLA authors often cite the need in modern warfare to control information, sometimes termed information blockade or information dominance. China is improving information and operational security, developing electronic warfare and information warfare capabilities, and denial and deception. Chinas information blockade likely envisions employment of military and non-military instruments of state power across all dimensions of the modern battlespace, including outer space.

Building Capacity for Conventional Precision Strike

Short-Range Ballistic Missiles (SRBMs) (< 1,000 km). According to DIA estimates, as of November 2007 the PLA had 990-1,070 SRBMs and is increasing its inventory at a rate of over 100 missiles per year. The PLAs first-generation SRBMs do not possess true precision strike capability; later generations have greater ranges and improved accuracy.

Medium-Range Ballistic Missiles (MRBMs) (1,000-3,000 km). The PLA is acquiring conventional MRBMs to increase the range to which it can conduct precision strikes, to include targeting naval ships, including aircraft carriers, operating far from Chinas shores.

Land-Attack Cruise Missiles (LACMs). China is developing air- and ground-launched LACMs, such as the YJ-63 and DH-10 systems for stand-off, precision strikes.

Air-to-Surface Missiles (ASMs). According to DIA estimates, China has a small number of tactical ASMs and precision-guided munitions, including all-weather, satellite and laser-guided bombs, and is pursuing improved airborne anti-ship capabilities.

Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCMs). The PLA Navy has or is acquiring nearly a dozen ASCM variants, ranging from the 1950s-era CSS-N-2 to the modern Russian-made SS-N-22 and SS-N-27B. The pace of ASCM research, development and production and of foreign procurement has accelerated over the past decade.

Anti-Radiation Weapons. The PLA has imported Israeli-made HARPY UCAVs and Russian-made antiradiation missiles (ARM), and is developing an ARM based on the Russian Kh-31P (AS-17) known domestically as the YJ-91.

Artillery-Delivered High Precision Munitions. The PLA is deploying the A-100 300 mm multiple rocket launcher (MRL) (100+ km range) and developing the WS-2 400 mm MRL (200 km range).

Strategic Capabilities

Nuclear Force Structure. China is qualitatively and quantitatively improving its strategic forces. These presently consist of: approximately 20 silo-based, liquid-fueled CSS-4 ICBMs (which constitute its primary nuclear means of holding continental U.S. targets at risk); approximately 20 liquid-fueled, limited range CSS-3 ICBMs; between 15-20 liquidfueled CSS-2 intermediate range ballistic missiles (IRBMs); upwards of 50 CSS-5 road mobile, solidfueled MRBMs (for regional deterrence missions); and, JL-1 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) on the XIA-class SSBN (although the operational status of the XIA is questionable).

By 2010, Chinas nuclear forces will likely comprise enhanced CSS-4s; CSS-3s; CSS-5s; solid-fueled, road-mobile DF-31 and DF31A ICBMs, which are being deployed to units of the Second Artillery Corps; and up to five JIN-class SSBNs, each carrying between 10 and 12 JL-2 SLBM. The addition of nuclear-capable forces with greater mobility and survivability, combined with ballistic missile defense countermeasures which China is researching including maneuvering re-entry vehicles (MaRV), multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles (MIRV), decoys, chaff, jamming, thermal shielding, and ASAT weapons will strengthen Chinas deterrent and enhance its capabilities for strategic strike. New air- and ground-launched cruise missiles that could perform nuclear missions would similarly improve the survivability, flexibility, and effectiveness of Chinas nuclear forces.

The introduction of more mobile systems will create new command and control challenges for Chinas leadership, now confronted with a different set of variables related to release and deployment authorities. For example, the PLA has only a limited capacity to communicate with submarines at sea and the PLA Navy has no experience in managing an SSBN fleet that performs strategic patrols. Limited insights on how the Second Artillery Corps, which controls Chinas land-based nuclear forces, may be seeking to address these issues can be derived from recent missile forces training which, as described by Chinas state-owned press, has begun to include scenarios in which missile batteries lose communication links with higher echelons and other situations that would require commanders to choose alternative launch locations.

Chinas 2006 Defense White Paper states that: 1) the purpose of Chinas nuclear force is to deter other countries from using or threatening to use nuclear weapons against China; 2) China upholds the principles of counterattack in self-defense and limited development of nuclear weapons; and, 3) China has never entered into and will never enter into a nuclear arms race with any other country. The document reiterated Chinas commitment to a declaratory policy of no first use (bu shouxian shiyong - 不首先使用 of nuclear weapons at any time and under any circumstances, and states China unconditionally undertakes not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states or nuclear weapon-free zones. Doctrinal materials suggest additional missions for Chinas nuclear forces include deterring conventional attacks against PRC nuclear assets or conventional attacks with WMD-like effects, reinforcing Chinas great power status, and increasing freedom of action by limiting the extent to which others can coerce China with nuclear threats.

of nuclear weapons at any time and under any circumstances, and states China unconditionally undertakes not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states or nuclear weapon-free zones. Doctrinal materials suggest additional missions for Chinas nuclear forces include deterring conventional attacks against PRC nuclear assets or conventional attacks with WMD-like effects, reinforcing Chinas great power status, and increasing freedom of action by limiting the extent to which others can coerce China with nuclear threats.

Given the above missions for Chinas nuclear forces, the conditions under which Chinas no first use policy applies are unclear. The PRC government has provided public and private assurances that its no first use policy has not and will not change, and doctrinal materials indicate internal PLA support for this policy. Nevertheless, periodic PRC military and civilian academic debates have occurred over the future of Chinas nuclear doctrine, to question whether a no first use policy supports or detracts from Chinas deterrent, and whether or not no first use should remain in place, adding a further layer of ambiguity to Chinas strategic intentions for its nuclear forces.

Space and Counterspace

Chinas space activities and capabilities, including ASAT programs, have significant implications for anti-access/area denial in Taiwan Strait contingencies and beyond. China further views the development of space and counter-space capabilities as bolstering national prestige and, like nuclear weapons, demonstrating the attributes of a world power.

Reconnaissance. China is deploying advanced imagery, reconnaissance, and Earth resource systems with military applications. Examples include the Ziyuan-2 series, the Yaogan-1 and -2, the Haiyang-1B, the CBERS-1 and -2 satellites, and the Huanjing disaster/environmental monitoring satellite constellation. China is planning eleven satellites in the Huanjing program capable of visible, infrared, multi-spectral, and synthetic aperture radar imaging. In the next decade, Beijing most likely will field radar, ocean surveillance, and high-resolution photoreconnaissance satellites. In the interim, China probably will rely on commercial satellite imagery to supplement existing coverage.

Navigation and Timing. China has launched five BeiDou satellites with an accuracy of 20 meters over China and surrounding areas. China also uses GPS and GLONASS navigation satellite systems, and has invested in the EUs Galileo navigation system. However, the role of non-European countries in Galileo currently is unsettled, as the Europeans are focusing on internal funding issues.

Manned Space and Lunar Programs. In October 2005, China completed its second manned space mission and Chinese astronauts conducted their first experiments in space. In October 2007, China launched its first lunar orbiter, the Change 1. Press reports indicate China will perform its first space walk in 2008, and rendezvous and docking in 2009-2012. Chinas goal is to have a manned space station and conduct a lunar landing, both by 2020.

Communications. China increasingly uses satellites, including some obtained from foreign providers, like INTELSAT and INMARSAT, for communications, may be developing a system of data relay satellites to support global coverage, and has reportedly acquired mobile data reception equipment that could support rapid data transmission to deployed military forces.

Small Satellites. Since 2000, China has launched a number of small satellites, including oceanographic research, imagery, and environmental research satellites. China has also established dedicated small satellite design and production facilities, and is developing microsatellites weighing less than 100 kilograms for remote sensing, and networks of imagery and radar satellites. These developments could allow for a rapid reconstitution or expansion of Chinas satellite force in the event of any disruption in coverage, given an adequate supply of boosters. Beijings efforts to develop small, rapidreaction space launch vehicles currently appears to be stalled.

Anti-Satellite (ASAT) Weapons. In January 2007, China successfully tested a direct-ascent ASAT missile against a PRC weather satellite, demonstrating its ability to attack satellites in low- Earth orbit. The direct-ascent ASAT system is one component of a multi-dimensional program to limit or prevent the use of space-based assets by its potential adversaries during times of crisis or conflict.

In a PLA National Defense University book, Joint Space War Campaigns (2005), author Colonel Yuan Zelu writes:

[The] goal of a space shock and awe strike is [to] deter the enemy, not to provoke the enemy into combat. For this reason, the objectives selected for strike must be few and precise . . .[for example] on important information sources, command and control centers, communications hubs, and other objectives. This will shake the structure of the opponents operational system of organization and will create huge psychological impact on the opponents policymakers.

Chinas nuclear arsenal has long provided Beijing with an inherent ASAT capability; the extent to which Chinas leaders have thought through the consequences of nuclear use in outer space or of nuclear EMP to degrade terrestrial communications equipment is unclear. UHF-band satellite communications jammers acquired from Ukraine in the late 1990s and probable indigenous systems give China today the capacity to jam common satellite communications bands and GPS receivers. In addition to the direct-ascent ASAT program demonstrated in January 2007, China is developing other technologies and concepts for kinetic and directed-energy (e.g., lasers and radio frequency) weapons for ASAT missions. Citing the requirements of its manned and lunar space programs, China is improving its ability to track and identify satellites a prerequisite for effective, precise counterspace operations.

Information Warfare. There has been much writing on information warfare among Chinas military thinkers, who indicate a strong conceptual understanding of its methods and uses. For example, a November 2006 Liberation Army Daily commentator argued:

[The] mechanism to get the upper hand of the enemy in a war under conditions of informatization finds prominent expression in whether or not we are capable of using various means to obtain information and of ensuring the effective circulation of information; whether or not we are capable of making full use of the permeability, sharable property, and connection of information to realize the organic merging of materials, energy, and information to form a combined fighting strength; [and,] whether or not we are capable of applying effective means to weaken the enemy sides information superiority and lower the operational efficiency of enemy information equipment.

The PLA is investing in electronic countermeasures, defenses against electronic attack (e.g., electronic and infrared decoys, angle reflectors, and false target generators), and CNO. Chinas CNO concepts include CNA, computer network exploitation (CNE), and computer network defense (CND). The PLA sees CNO as critical to achieving electromagnetic dominance early in a conflict. Although there is no evidence of a formal PLA CNO doctrine, PLA theorists have coined the term Integrated Network Electronic Warfare (wangdian yitizhan - 网电一体 战 to prescribe the use of electronic warfare, CNO, and kinetic strikes to disrupt battlefield network information systems that support an adversarys warfighting and power projection capabilities.

to prescribe the use of electronic warfare, CNO, and kinetic strikes to disrupt battlefield network information systems that support an adversarys warfighting and power projection capabilities.

The PLA has established information warfare units to develop viruses to attack enemy computer systems and networks, and tactics and measures to protect friendly computer systems and networks. In 2005, the PLA began to incorporate offensive CNO into its exercises, primarily in first strikes against enemy networks.

Power Projection Modernization Beyond Taiwan

In a speech at the March 2006 National Peoples Congress, then-PLA Chief of the General Staff General Liang Guanglie stated that one must attend to the effective implementation of the historical mission of our forces at this new stage in this new century . . . preparations for a multitude of military hostilities must be done in concrete manner, [and] . . . competence in tackling multiple security threats and accomplishing a diverse range of military missions must be stepped up.

China continues to invest in military programs designed to improve extended-range power projection. Current trends in Chinas military capabilities are a major factor in changing East Asian military balances, and could provide China with a force capable of prosecuting a range of military operations in Asia well beyond Taiwan. Given the apparent absence of direct threats from other nations, the purposes to which Chinas current and future military power will be applied remain unknown. These capabilities will increase Beijings options for military coercion to press diplomatic advantage, advance interests, or resolve disputes in its favor.

Official documents and the writings of PLA military strategists suggest Beijing is increasingly surveying the strategic landscape beyond Taiwan. Some PLA analysts have explored the geopolitical value of Taiwan in extending Chinas maritime defensive perimeter and improving its ability to influence regional sea lines of communication. For example, the PLA Academy of Military Science text, Science of Military Strategy (2000), states:

If Taiwan should be alienated from the mainland, not only [would] our natural maritime defense system lose its depth, opening a sea gateway to outside forces, but also a large area of water territory and rich resources of ocean resources would fall into the hands of others.... [O]ur line of foreign trade and transportation which is vital to Chinas opening up and economic development will be exposed to the surveillance and threats of separatists and enemy forces, and China will forever be locked to the west of the first chain of islands in the West Pacific.

Chinas 2006 Defense White Paper similarly raises concerns about resources and transportation links when it states that security issues related to energy, resources, finance, information, and international shipping routes are mounting. The related desire to protect energy investments in Central Asia and land lines of communication could also provide an incentive for military investment or intervention if instability surfaces in the region. Disagreements that remain with Japan over maritime claims in the East China Sea and with several Southeast Asian claimants to all or parts of the Spratly and Paracel Islands in the South China Sea could lead to renewed tensions in these areas. Instability on the Korean Peninsula likewise could produce a regional crisis in which Beijing would face a choice between diplomatic or military responses.

Analysis of Chinas weapons acquisitions also suggests China is looking beyond Taiwan as it builds its force. For example, new missile units outfitted with conventional theater-range missiles at various locations in China could be used in a variety of non- Taiwan contingencies. AEW&C and aerial-refueling programs would permit extended air operations into the South China Sea and beyond.

Advanced destroyers and submarines reflect Beijings desire to protect and advance its maritime interests up to and beyond the second island chain. Potential expeditionary forces (three airborne divisions, two amphibious infantry divisions, two marine brigades, about seven special operations groups, and one regimental-size reconnaissance element in the Second Artillery) are improving with the introduction of new equipment, better unit-level tactics, and greater coordination of joint operations. Over the long term, improvements in Chinas C4ISR, including space-based and over-the-horizon sensors, could enable Beijing to identify, track, and target military activities deep into the western Pacific Ocean.

For the whole report, see http://www.defenselink.mil/pubs/pdfs/China_Military_Report_08.pdf

ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS

Military Power of the Peoples Republic of China 2008

Chapter Four

Force Modernization Goals and Trends

China pursues a three-step development strategy in modernizing its national defense . . . . The first step is to lay a solid foundation by 2010, the second is to make major progress around 2020, and the third is to basically reach the strategic goal of building informatized armed forces and being capable of winning informatized wars by the mid-21st century.

Chinas National Defense in 2006

Overview

Chinas leaders have stated their intentions and allocated resources to pursue broad-based military transformation that encompasses force-wide professionalization; improved training; more robust, realistic joint exercises; and, accelerated acquisition and development of modern conventional and nuclear weapons. Chinas military appears focused on assuring the capability to prevent Taiwan independence and, if Beijing were to decide to adopt such an approach, to compel the island to negotiate a settlement on Beijings terms. At the same time, China is laying the foundation for a force able to accomplish broader regional and global objectives.

The U.S. Intelligence Community estimates China will take until the end of this decade or longer to produce a modern force capable of defeating a moderate-size adversary. China will not be able to project and sustain small military units far beyond China before 2015, and will not be able to project and sustain large forces in combat operations far from China until well into the following decade. In building its forces, Chinas leaders stress asymmetric strategies to leverage Chinas advantages while exploiting the perceived vulnerabilities of potential opponents using so-called assassins mace programs (e.g., counterspace and cyberwarfare programs). The PLA hopes eventually to fuse service-level capabilities with an integrated network for C4ISR, a new command structure, and a joint logistics system. However, it continues to face deficiencies in inter-service cooperation and actual experience in joint exercises and combat operations.

Potential for Miscalculation

As PLA modernization progresses, three misperceptions could lead to miscalculation or crisis. First, other countries could underestimate the extent to which PLA forces have improved. Second, Chinas leaders could overestimate the proficiency of their forces by assuming new systems are fully operational, adeptly operated, adequately maintained, and well integrated with existing or other new capabilities. Third, Chinas leaders may underestimate the effects of their decisions on the security perceptions and responses of other regional actors.

Emerging Anti-Access/Area Denial Capabilities

As part of its planning for a Taiwan contingency, China is prioritizing measures to deter or counter third-party intervention in any future cross-Strait crisis. Chinas approach to dealing with this challenge centers on what DoDs 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review refers to as disruptive capabilities: forces and operational concepts aimed at deterring or denying the entry of enemy forces into a theater of operations (anti-access), and limited duration denial of enemy freedom of action in a theater of operations (area denial). In this context, the PLA appears engaged in a sustained effort to develop the capability to interdict or attack, at long ranges, military forces particularly air or maritime forces that might deploy or operate within the western Pacific. Increasingly, Chinas anti-access/area denial forces overlap, providing multiple layers of offensive systems, utilizing the sea, air, space, and cyber-space.

PLA planners are focused on targeting surface ships at long ranges from Chinas shores. Analyses of current and projected force structure improvements suggest that China is seeking the capacity to hold surface ships at risk through a layered capability reaching out to the second island chain (i.e., the islands extending south and east from Japan, to and beyond Guam in the western Pacific Ocean). One area of investment involves combining conventionally-armed ASBMs based on the CSS-5 (DF-21) airframe, C4ISR for geo-location and tracking of targets, and onboard guidance systems for terminal homing to strike surface ships on the high seas or their onshore support infrastructure. This capability would have particular significance, as it would provide China with preemptive and coercive options in a regional crisis.

PRC military analysts have also concluded that logistics and mobilization are potential vulnerabilities in modern warfare, given the requirements for precision in coordinating transportation, communications, and logistics networks. To threaten regional bases and logistics points, China could employ SRBM/MRBMs, land-attack cruise missiles, special operations forces, and computer network attack (CNA). Strike aircraft, when enabled by aerial refueling, could engage distant targets using air-launched cruise missiles equipped with a variety of terminal-homing warheads.

Chinas emerging local sea denial capabilities mines, submarines, maritime strike aircraft, and modern surface combatants equipped with advanced ASCMs provide a supporting layer of defense for its long-range anti-access systems. Acquisition and development of the KILO, SONG, SHANG, and YUAN-class submarines illustrates the importance the PLA places on undersea warfare for sea denial. In the past ten years, China has deployed ten new classes of ships. The purchase of SOVREMENNYY II-class DDGs and indigenous production of the LUYANG I/ LUYANG II DDGs equipped with long-range ASCM and SAM systems, for example, demonstrate a continuing emphasis on improving anti-surface warfare, combined with mobile, widearea air control.

The air and air defense component of anti-access/ area-denial includes SAMs such as the HQ-9, SA-10, SA-20 (which has a reported limited ballistic and cruise missile defense capability), and the extended-range SA-20 PMU2. Beijing will also use Russian-built and domestic fourth-generation aircraft (e.g., Su-27 and Su-30 variants, and the indigenous F-10 multirole fighter). The PLA Navy would employ Russian Su-30MK2 fighters, armed with AS-17/Kh-31A anti-ship missiles. Acquisition of an air refueling platform like the Russian IL-78 would extend operational ranges for PLAAF and PLA Navy strike aircraft armed with precision munitions, thereby increasing the threat to surface and air forces, bases, and logistics nodes distant from Chinas coast. Additionally, acquisition and development of longer-range unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs), including the Israeli HARPY, expands Chinas options for long-range reconnaissance and strike.

A final element of an emerging area denial/anti access strategy includes the electromagnetic and information spheres. PLA authors often cite the need in modern warfare to control information, sometimes termed information blockade or information dominance. China is improving information and operational security, developing electronic warfare and information warfare capabilities, and denial and deception. Chinas information blockade likely envisions employment of military and non-military instruments of state power across all dimensions of the modern battlespace, including outer space.

Building Capacity for Conventional Precision Strike

Short-Range Ballistic Missiles (SRBMs) (< 1,000 km). According to DIA estimates, as of November 2007 the PLA had 990-1,070 SRBMs and is increasing its inventory at a rate of over 100 missiles per year. The PLAs first-generation SRBMs do not possess true precision strike capability; later generations have greater ranges and improved accuracy.

Medium-Range Ballistic Missiles (MRBMs) (1,000-3,000 km). The PLA is acquiring conventional MRBMs to increase the range to which it can conduct precision strikes, to include targeting naval ships, including aircraft carriers, operating far from Chinas shores.

Land-Attack Cruise Missiles (LACMs). China is developing air- and ground-launched LACMs, such as the YJ-63 and DH-10 systems for stand-off, precision strikes.

Air-to-Surface Missiles (ASMs). According to DIA estimates, China has a small number of tactical ASMs and precision-guided munitions, including all-weather, satellite and laser-guided bombs, and is pursuing improved airborne anti-ship capabilities.

Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCMs). The PLA Navy has or is acquiring nearly a dozen ASCM variants, ranging from the 1950s-era CSS-N-2 to the modern Russian-made SS-N-22 and SS-N-27B. The pace of ASCM research, development and production and of foreign procurement has accelerated over the past decade.

Anti-Radiation Weapons. The PLA has imported Israeli-made HARPY UCAVs and Russian-made antiradiation missiles (ARM), and is developing an ARM based on the Russian Kh-31P (AS-17) known domestically as the YJ-91.

Artillery-Delivered High Precision Munitions. The PLA is deploying the A-100 300 mm multiple rocket launcher (MRL) (100+ km range) and developing the WS-2 400 mm MRL (200 km range).

Strategic Capabilities

Nuclear Force Structure. China is qualitatively and quantitatively improving its strategic forces. These presently consist of: approximately 20 silo-based, liquid-fueled CSS-4 ICBMs (which constitute its primary nuclear means of holding continental U.S. targets at risk); approximately 20 liquid-fueled, limited range CSS-3 ICBMs; between 15-20 liquidfueled CSS-2 intermediate range ballistic missiles (IRBMs); upwards of 50 CSS-5 road mobile, solidfueled MRBMs (for regional deterrence missions); and, JL-1 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) on the XIA-class SSBN (although the operational status of the XIA is questionable).

By 2010, Chinas nuclear forces will likely comprise enhanced CSS-4s; CSS-3s; CSS-5s; solid-fueled, road-mobile DF-31 and DF31A ICBMs, which are being deployed to units of the Second Artillery Corps; and up to five JIN-class SSBNs, each carrying between 10 and 12 JL-2 SLBM. The addition of nuclear-capable forces with greater mobility and survivability, combined with ballistic missile defense countermeasures which China is researching including maneuvering re-entry vehicles (MaRV), multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles (MIRV), decoys, chaff, jamming, thermal shielding, and ASAT weapons will strengthen Chinas deterrent and enhance its capabilities for strategic strike. New air- and ground-launched cruise missiles that could perform nuclear missions would similarly improve the survivability, flexibility, and effectiveness of Chinas nuclear forces.

The introduction of more mobile systems will create new command and control challenges for Chinas leadership, now confronted with a different set of variables related to release and deployment authorities. For example, the PLA has only a limited capacity to communicate with submarines at sea and the PLA Navy has no experience in managing an SSBN fleet that performs strategic patrols. Limited insights on how the Second Artillery Corps, which controls Chinas land-based nuclear forces, may be seeking to address these issues can be derived from recent missile forces training which, as described by Chinas state-owned press, has begun to include scenarios in which missile batteries lose communication links with higher echelons and other situations that would require commanders to choose alternative launch locations.

Chinas 2006 Defense White Paper states that: 1) the purpose of Chinas nuclear force is to deter other countries from using or threatening to use nuclear weapons against China; 2) China upholds the principles of counterattack in self-defense and limited development of nuclear weapons; and, 3) China has never entered into and will never enter into a nuclear arms race with any other country. The document reiterated Chinas commitment to a declaratory policy of no first use (bu shouxian shiyong - 不首先使用

of nuclear weapons at any time and under any circumstances, and states China unconditionally undertakes not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states or nuclear weapon-free zones. Doctrinal materials suggest additional missions for Chinas nuclear forces include deterring conventional attacks against PRC nuclear assets or conventional attacks with WMD-like effects, reinforcing Chinas great power status, and increasing freedom of action by limiting the extent to which others can coerce China with nuclear threats.

of nuclear weapons at any time and under any circumstances, and states China unconditionally undertakes not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states or nuclear weapon-free zones. Doctrinal materials suggest additional missions for Chinas nuclear forces include deterring conventional attacks against PRC nuclear assets or conventional attacks with WMD-like effects, reinforcing Chinas great power status, and increasing freedom of action by limiting the extent to which others can coerce China with nuclear threats.Given the above missions for Chinas nuclear forces, the conditions under which Chinas no first use policy applies are unclear. The PRC government has provided public and private assurances that its no first use policy has not and will not change, and doctrinal materials indicate internal PLA support for this policy. Nevertheless, periodic PRC military and civilian academic debates have occurred over the future of Chinas nuclear doctrine, to question whether a no first use policy supports or detracts from Chinas deterrent, and whether or not no first use should remain in place, adding a further layer of ambiguity to Chinas strategic intentions for its nuclear forces.

Space and Counterspace

Chinas space activities and capabilities, including ASAT programs, have significant implications for anti-access/area denial in Taiwan Strait contingencies and beyond. China further views the development of space and counter-space capabilities as bolstering national prestige and, like nuclear weapons, demonstrating the attributes of a world power.

Reconnaissance. China is deploying advanced imagery, reconnaissance, and Earth resource systems with military applications. Examples include the Ziyuan-2 series, the Yaogan-1 and -2, the Haiyang-1B, the CBERS-1 and -2 satellites, and the Huanjing disaster/environmental monitoring satellite constellation. China is planning eleven satellites in the Huanjing program capable of visible, infrared, multi-spectral, and synthetic aperture radar imaging. In the next decade, Beijing most likely will field radar, ocean surveillance, and high-resolution photoreconnaissance satellites. In the interim, China probably will rely on commercial satellite imagery to supplement existing coverage.

Navigation and Timing. China has launched five BeiDou satellites with an accuracy of 20 meters over China and surrounding areas. China also uses GPS and GLONASS navigation satellite systems, and has invested in the EUs Galileo navigation system. However, the role of non-European countries in Galileo currently is unsettled, as the Europeans are focusing on internal funding issues.

Manned Space and Lunar Programs. In October 2005, China completed its second manned space mission and Chinese astronauts conducted their first experiments in space. In October 2007, China launched its first lunar orbiter, the Change 1. Press reports indicate China will perform its first space walk in 2008, and rendezvous and docking in 2009-2012. Chinas goal is to have a manned space station and conduct a lunar landing, both by 2020.

Communications. China increasingly uses satellites, including some obtained from foreign providers, like INTELSAT and INMARSAT, for communications, may be developing a system of data relay satellites to support global coverage, and has reportedly acquired mobile data reception equipment that could support rapid data transmission to deployed military forces.

Small Satellites. Since 2000, China has launched a number of small satellites, including oceanographic research, imagery, and environmental research satellites. China has also established dedicated small satellite design and production facilities, and is developing microsatellites weighing less than 100 kilograms for remote sensing, and networks of imagery and radar satellites. These developments could allow for a rapid reconstitution or expansion of Chinas satellite force in the event of any disruption in coverage, given an adequate supply of boosters. Beijings efforts to develop small, rapidreaction space launch vehicles currently appears to be stalled.

Anti-Satellite (ASAT) Weapons. In January 2007, China successfully tested a direct-ascent ASAT missile against a PRC weather satellite, demonstrating its ability to attack satellites in low- Earth orbit. The direct-ascent ASAT system is one component of a multi-dimensional program to limit or prevent the use of space-based assets by its potential adversaries during times of crisis or conflict.

In a PLA National Defense University book, Joint Space War Campaigns (2005), author Colonel Yuan Zelu writes:

[The] goal of a space shock and awe strike is [to] deter the enemy, not to provoke the enemy into combat. For this reason, the objectives selected for strike must be few and precise . . .[for example] on important information sources, command and control centers, communications hubs, and other objectives. This will shake the structure of the opponents operational system of organization and will create huge psychological impact on the opponents policymakers.

Chinas nuclear arsenal has long provided Beijing with an inherent ASAT capability; the extent to which Chinas leaders have thought through the consequences of nuclear use in outer space or of nuclear EMP to degrade terrestrial communications equipment is unclear. UHF-band satellite communications jammers acquired from Ukraine in the late 1990s and probable indigenous systems give China today the capacity to jam common satellite communications bands and GPS receivers. In addition to the direct-ascent ASAT program demonstrated in January 2007, China is developing other technologies and concepts for kinetic and directed-energy (e.g., lasers and radio frequency) weapons for ASAT missions. Citing the requirements of its manned and lunar space programs, China is improving its ability to track and identify satellites a prerequisite for effective, precise counterspace operations.

Information Warfare. There has been much writing on information warfare among Chinas military thinkers, who indicate a strong conceptual understanding of its methods and uses. For example, a November 2006 Liberation Army Daily commentator argued:

[The] mechanism to get the upper hand of the enemy in a war under conditions of informatization finds prominent expression in whether or not we are capable of using various means to obtain information and of ensuring the effective circulation of information; whether or not we are capable of making full use of the permeability, sharable property, and connection of information to realize the organic merging of materials, energy, and information to form a combined fighting strength; [and,] whether or not we are capable of applying effective means to weaken the enemy sides information superiority and lower the operational efficiency of enemy information equipment.

The PLA is investing in electronic countermeasures, defenses against electronic attack (e.g., electronic and infrared decoys, angle reflectors, and false target generators), and CNO. Chinas CNO concepts include CNA, computer network exploitation (CNE), and computer network defense (CND). The PLA sees CNO as critical to achieving electromagnetic dominance early in a conflict. Although there is no evidence of a formal PLA CNO doctrine, PLA theorists have coined the term Integrated Network Electronic Warfare (wangdian yitizhan - 网电一体 战

to prescribe the use of electronic warfare, CNO, and kinetic strikes to disrupt battlefield network information systems that support an adversarys warfighting and power projection capabilities.

to prescribe the use of electronic warfare, CNO, and kinetic strikes to disrupt battlefield network information systems that support an adversarys warfighting and power projection capabilities.The PLA has established information warfare units to develop viruses to attack enemy computer systems and networks, and tactics and measures to protect friendly computer systems and networks. In 2005, the PLA began to incorporate offensive CNO into its exercises, primarily in first strikes against enemy networks.

Power Projection Modernization Beyond Taiwan

In a speech at the March 2006 National Peoples Congress, then-PLA Chief of the General Staff General Liang Guanglie stated that one must attend to the effective implementation of the historical mission of our forces at this new stage in this new century . . . preparations for a multitude of military hostilities must be done in concrete manner, [and] . . . competence in tackling multiple security threats and accomplishing a diverse range of military missions must be stepped up.

China continues to invest in military programs designed to improve extended-range power projection. Current trends in Chinas military capabilities are a major factor in changing East Asian military balances, and could provide China with a force capable of prosecuting a range of military operations in Asia well beyond Taiwan. Given the apparent absence of direct threats from other nations, the purposes to which Chinas current and future military power will be applied remain unknown. These capabilities will increase Beijings options for military coercion to press diplomatic advantage, advance interests, or resolve disputes in its favor.

Official documents and the writings of PLA military strategists suggest Beijing is increasingly surveying the strategic landscape beyond Taiwan. Some PLA analysts have explored the geopolitical value of Taiwan in extending Chinas maritime defensive perimeter and improving its ability to influence regional sea lines of communication. For example, the PLA Academy of Military Science text, Science of Military Strategy (2000), states:

If Taiwan should be alienated from the mainland, not only [would] our natural maritime defense system lose its depth, opening a sea gateway to outside forces, but also a large area of water territory and rich resources of ocean resources would fall into the hands of others.... [O]ur line of foreign trade and transportation which is vital to Chinas opening up and economic development will be exposed to the surveillance and threats of separatists and enemy forces, and China will forever be locked to the west of the first chain of islands in the West Pacific.

Chinas 2006 Defense White Paper similarly raises concerns about resources and transportation links when it states that security issues related to energy, resources, finance, information, and international shipping routes are mounting. The related desire to protect energy investments in Central Asia and land lines of communication could also provide an incentive for military investment or intervention if instability surfaces in the region. Disagreements that remain with Japan over maritime claims in the East China Sea and with several Southeast Asian claimants to all or parts of the Spratly and Paracel Islands in the South China Sea could lead to renewed tensions in these areas. Instability on the Korean Peninsula likewise could produce a regional crisis in which Beijing would face a choice between diplomatic or military responses.

Analysis of Chinas weapons acquisitions also suggests China is looking beyond Taiwan as it builds its force. For example, new missile units outfitted with conventional theater-range missiles at various locations in China could be used in a variety of non- Taiwan contingencies. AEW&C and aerial-refueling programs would permit extended air operations into the South China Sea and beyond.

Advanced destroyers and submarines reflect Beijings desire to protect and advance its maritime interests up to and beyond the second island chain. Potential expeditionary forces (three airborne divisions, two amphibious infantry divisions, two marine brigades, about seven special operations groups, and one regimental-size reconnaissance element in the Second Artillery) are improving with the introduction of new equipment, better unit-level tactics, and greater coordination of joint operations. Over the long term, improvements in Chinas C4ISR, including space-based and over-the-horizon sensors, could enable Beijing to identify, track, and target military activities deep into the western Pacific Ocean.