FOOLS_NIGHTMARE

ELITE MEMBER

- Joined

- Sep 26, 2018

- Messages

- 18,063

- Reaction score

- 12

- Country

- Location

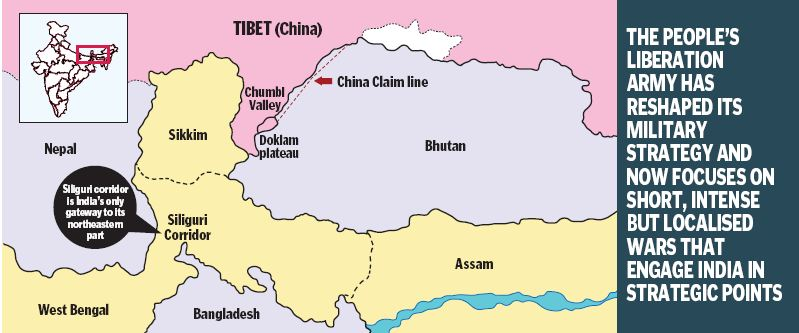

Any push down the Chumbi Valley and then control of the Siliguri corridor will cut off the northeastern States

For India, the message from the north of the Himalayas is loud and unambiguous — China is now refashioning its border policy and is likely to put increasing pressures on India in the northeastern sector in addition to the ongoing hostilities in the Ladakh area. The spectre in the south of the McMahon Line is more dangerous for New Delhi than what it has been facing in the Galwan Valley or the Pangong Tso lake area because increasing Chinese belligerence here holds out a threat to Arunachal Pradesh and the whole of northeastern India.

There are reports that China has set up a village at the northeastern boundary of the Doklam plateau, an area said to be belonging to Bhutan. Secondly, construction of Chinese villages close to the tri-junction of India, China and Bhutan in western Arunachal Pradesh has been reported. These villages are a few kilometre off the Bumla Pass, which is strategically extremely important for India.

Beijing is slowly unfurling its India policy. There is now a lull in hostilities in the Ladakh sector although armies of the two countries are now standing eyeball to eyeball. But China will always aim to cut off the Indian army’s outpost at Daulat Beg Oldi, which is very near the Karakoram Pass and thus quite close to China’s Xinjiang province where Uighur militancy and consequent Chinese governmental crackdown is now in full swing. Another area Beijing will try to cut off in the event of a full-scale war is Leh, the headquarters of Ladakh, which is just seven hours distance from the Pangong Tso lake.

Recent media reports from the Arunachal Pradesh sector suggest movement of Chinese troops in their depth areas, ie, around 20 km from the Line of Actual Control (LAC). China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been carrying on regular patrols and they are often coming very close to Indian areas. The reports, obviously on army briefings, have mentioned three areas — Asaphila, Tuting Axis and Fish Tail-2, opposite of which renewed Chinese military activities have come to light.

China claims the whole of Arunachal Pradesh. Its continued interest in the Doklam plateau of Bhutan does not bode well for West Bengal and the whole of northeastern India. In fact, China’s policy in the south of the McMohan Line combines Arunachal Pradesh and Bhutan. With this end in view, Beijing has staked claims to Bhutan’s Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary, which adjoins the West Kameng and Tawang districts of Arunachal Pradesh.

Even in any short duration war, China’s first target in the Arunachal Pradesh sector will be the Tawang monastery, which is only second in importance to Tibetan Buddhism after the monastery of Lhasa. In the 1962 war, China had captured this whole tract, including the Tawang monastery, up to Bomdila, a place very near to Tezpur in Assam. The Chinese strategic plan will be clear when it is kept in mind that Tawang is situated in the northeast of the Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary.

Strategically speaking, Beijing is expected to give more emphasis to the McMahon Line sector than the Ladakh area in the coming days. It is because of the fact that military manoeuvres are easier here than in the Ladakh area. For China, the central focus would be on the Chumbi Valley. It is an arrow like protrusion of a part of southern Tibet separating Bhutan from the Indian State of Sikkim. It is the tri-junction of China, India and Bhutan and enjoys unparalleled strategic importance in the whole of eastern Himalayas. It is very near to the Siliguri corridor, called the Chicken’s Neck due to its long and narrow shape, which is India’s only gateway to its northeastern part. Any Chinese push down the Chumbi Valley and then control of the Siliguri corridor will cut off all the northeastern States of India and will also put Kolkata under grave danger.

China has staked claims to Bhutanese territories in the central and western parts of the country — 495 square km in the Jakarlung and Pasamlung valleys in the central sector and 269 square km in the western sector, which includes the Doklam plateau. It is significant that Chinese claims in the western sector include other strategically important areas like Charithang, Sinchulimpa and Dramana pasture lands. Clearly, Beijing is working on a plan. Inclusion of all these areas will make the Chumbi Valley a vast expanse, ideal for any military move.

By staking a claim to the Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary, Beijing is trying to send across three messages to Thimpu. First, it wants to have another clear foothold near Arunachal Pradesh. Secondly, it is trying to coerce Bhutan to sign a boundary agreement, which will pave the way for Chinese presence in the Doklam plateau. Thirdly, it is a warning to Bhutan not to lean towards the Indian side.

The People’s Liberation Army has reshaped its military strategy. It now focuses on short, intense but localised wars. With this end in view, it has modernised the Lhasa Gonggar airport, a base of the PLAAF, with an upgraded apron for accommodating more fighter aircraft. These aircraft are now kept in significantly strengthened shelters so that enemy missiles and bombs can do no harm to them.

telanganatoday.com

telanganatoday.com

The article was written in 2021 but is still valid today.

For India, the message from the north of the Himalayas is loud and unambiguous — China is now refashioning its border policy and is likely to put increasing pressures on India in the northeastern sector in addition to the ongoing hostilities in the Ladakh area. The spectre in the south of the McMahon Line is more dangerous for New Delhi than what it has been facing in the Galwan Valley or the Pangong Tso lake area because increasing Chinese belligerence here holds out a threat to Arunachal Pradesh and the whole of northeastern India.

There are reports that China has set up a village at the northeastern boundary of the Doklam plateau, an area said to be belonging to Bhutan. Secondly, construction of Chinese villages close to the tri-junction of India, China and Bhutan in western Arunachal Pradesh has been reported. These villages are a few kilometre off the Bumla Pass, which is strategically extremely important for India.

Salami Slicing

It will not be unfair to christen these Chinese moves as attempts of ‘salami slicing’ as described by General Bipin Rawat, India’s Chief of the Defence Staff. This means slow and unobtrusive infiltration into other’s territories.Beijing is slowly unfurling its India policy. There is now a lull in hostilities in the Ladakh sector although armies of the two countries are now standing eyeball to eyeball. But China will always aim to cut off the Indian army’s outpost at Daulat Beg Oldi, which is very near the Karakoram Pass and thus quite close to China’s Xinjiang province where Uighur militancy and consequent Chinese governmental crackdown is now in full swing. Another area Beijing will try to cut off in the event of a full-scale war is Leh, the headquarters of Ladakh, which is just seven hours distance from the Pangong Tso lake.

Himalayan Strategies

This is China’s military strategy in the Himalayas – engaging India in some strategic points. Let us now consider the other end of the spectrum – the northeastern sector of the Indo-China border.Recent media reports from the Arunachal Pradesh sector suggest movement of Chinese troops in their depth areas, ie, around 20 km from the Line of Actual Control (LAC). China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been carrying on regular patrols and they are often coming very close to Indian areas. The reports, obviously on army briefings, have mentioned three areas — Asaphila, Tuting Axis and Fish Tail-2, opposite of which renewed Chinese military activities have come to light.

China claims the whole of Arunachal Pradesh. Its continued interest in the Doklam plateau of Bhutan does not bode well for West Bengal and the whole of northeastern India. In fact, China’s policy in the south of the McMohan Line combines Arunachal Pradesh and Bhutan. With this end in view, Beijing has staked claims to Bhutan’s Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary, which adjoins the West Kameng and Tawang districts of Arunachal Pradesh.

Even in any short duration war, China’s first target in the Arunachal Pradesh sector will be the Tawang monastery, which is only second in importance to Tibetan Buddhism after the monastery of Lhasa. In the 1962 war, China had captured this whole tract, including the Tawang monastery, up to Bomdila, a place very near to Tezpur in Assam. The Chinese strategic plan will be clear when it is kept in mind that Tawang is situated in the northeast of the Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary.

Strategically speaking, Beijing is expected to give more emphasis to the McMahon Line sector than the Ladakh area in the coming days. It is because of the fact that military manoeuvres are easier here than in the Ladakh area. For China, the central focus would be on the Chumbi Valley. It is an arrow like protrusion of a part of southern Tibet separating Bhutan from the Indian State of Sikkim. It is the tri-junction of China, India and Bhutan and enjoys unparalleled strategic importance in the whole of eastern Himalayas. It is very near to the Siliguri corridor, called the Chicken’s Neck due to its long and narrow shape, which is India’s only gateway to its northeastern part. Any Chinese push down the Chumbi Valley and then control of the Siliguri corridor will cut off all the northeastern States of India and will also put Kolkata under grave danger.

Ideal Launch Pad

This is where Bhutan’s Doklam plateau becomes important for China. The Chumbi Valley gives China an ideal launch pad for any decisive incursion into India. But the topography of the valley provides a barrier to this adventurism also. The valley is extremely narrow, only 30 miles wide in its narrowest stretch for military manoeuvres and, therefore, Beijing has been trying to expand the Chumbi Valley by incorporating the neighbouring Doklam plateau into it.China has staked claims to Bhutanese territories in the central and western parts of the country — 495 square km in the Jakarlung and Pasamlung valleys in the central sector and 269 square km in the western sector, which includes the Doklam plateau. It is significant that Chinese claims in the western sector include other strategically important areas like Charithang, Sinchulimpa and Dramana pasture lands. Clearly, Beijing is working on a plan. Inclusion of all these areas will make the Chumbi Valley a vast expanse, ideal for any military move.

By staking a claim to the Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary, Beijing is trying to send across three messages to Thimpu. First, it wants to have another clear foothold near Arunachal Pradesh. Secondly, it is trying to coerce Bhutan to sign a boundary agreement, which will pave the way for Chinese presence in the Doklam plateau. Thirdly, it is a warning to Bhutan not to lean towards the Indian side.

The People’s Liberation Army has reshaped its military strategy. It now focuses on short, intense but localised wars. With this end in view, it has modernised the Lhasa Gonggar airport, a base of the PLAAF, with an upgraded apron for accommodating more fighter aircraft. These aircraft are now kept in significantly strengthened shelters so that enemy missiles and bombs can do no harm to them.

A new threat from China

Any push down the Chumbi Valley and then control of the Siliguri corridor will cut off the northeastern States

The article was written in 2021 but is still valid today.

Last edited: