A

A.Rahman

GUEST

<div class='bbimg'>

</div>

</div>

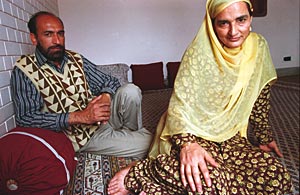

Sheikh Zahoor Ahmed and his wife Dilshad sent their son abroad to escape Kashmir's cycle of violence

Monday, May. 20, 2002

Procreation implies optimism. Mothers and fathers must believe that society will provide a haven, an environment in which their children will thrive. What does it say, then, if parents no longer have that faith? If rather than raise their children themselves, parents would send their beloved to far-flung corners of the world, anywhere, really, to escape the carnage of Kashmir?

Dilshada and Zahoor Ahmed Sheikh faced that bleak reality when their son Khalid was 16. Khalid was looking up to some dangerous role models: a few older friends who had gone across the border to Pakistan to join up with the anti-India insurgency raging in Kashmir. He developed a schoolboy enthusiasm for AK-47s. Then Khalid announced there was no point studying because, in his words, "Everyone is going to die anyway." The couple had to make a decision. "We summoned up our courage," says mother Dilshada, "and sent him away."

It was the best thing that could have happened to a young Kashmiri in the 1990s. Ten years later, Khalid has a master's in business administration from Ohio University and is planning to go back to the U.S. for an additional degree, this one in finance. His friends who stayed behind to study medicine or law don't have a hope of practicing their professions: there are no jobs in Kashmir. Of his ten closest schoolmates, four joined the militancyââ¬âat least one died in actionââ¬âand others left town. When Khalid returns for holidays, he finds Kashmir stiflingly oppressive. Last month, he and his 49-year-old father were ordered out of their car by Indian soldiers for a security check. "They were so rude, I couldn't believe my father was being all soft and pleading, giving them explanations. But he told me later: 'This is the way things are here.'"

To call Kashmir the subcontinent's West Bank or Gaza Strip would be a stretch. The Kashmir Valley, the heart and soul of the territory, is one of the earth's lovelier places. Many Kashmiris are poor, but no one lives in 50-year-old refugee settlements. Unlike the Palestinians, they have a homeland.

But it's a homeland more and more are abandoning because Kashmir is where the tension between India and Pakistan always surfaces. Kashmir is the biggest bit of unfinished business from the partition of the subcontinent 53 years ago. Pakistan still believes it shouldn't have gone to India, the Indians will probably never let it go, and both sides are more than willing to fight over itââ¬âpotentially with atomic warheads. Two of the three wars fought between the two countries started off in Kashmir. Since the beginning of the year, both have mobilized their armies along their common border and kept them at high alert, a state of war readiness prompted by a December terrorist attack intended to blow up the Parliament building in New Delhi. And last week, 30 people were killed by some fidayeen, a suicide squad that sneaked in from Pakistan, setting off a fresh round of accusations, the possible expulsion of Pakistan's ambassador from New Delhi, and some heavy shelling at the Line of Control, the de facto border that splits Kashmir.

Stuck in the middle, Kashmiris have either stolidly borne up, joined the separatist militants, or been forced to find a decent life far away from family, the mother tongue and the mountains, orchards and idyllic lakes. "The militancy turned out to be a blessing for me," says Khalid. "If there had been no violence, I would have studied at home and joined the family business." Khalid's family has a substantial textile and carpet business. They could afford to buy their son freedom.

Most other Kashmiris have no such luck. Their home is the disputed prize in what may be the most dangerous conflict on earth. In the early months of 1999, Pakistani soldiers took control of a mountain ridge on the Indian side of the Line of Control. In the spring, when they were discovered, that sparked the Kargil War, named for the region where it was fought. Both sides had tested nukes a few months earlier; last week in Washington, Bruce Riedel, senior director at the National Security Council, revealed that the Pakistani army, without informing its own government, had mobilized its nuclear arsenal at the height of the conflict. Former U.S. President Clinton persuaded then-Pakistani Prime Minister Mian Nawaz Sharif to withdraw his forces, ending what appears to be one of the closest brushes with nuclear war since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

Last week, the countries went back to the brink. Shortly before dawn on Tuesday, three men in army uniforms, who were later identified as Pakistani citizens, boarded a Himachal Roadways passenger bus on its way to Jammu, winter capital of India's Jammu and Kashmir state. On board for 15 minutes, the men asked to be dropped off near an army barracks. After the bus had stopped, the men ordered the sleepy passengers to the back of the vehicle and opened fire. They tossed a grenade into the bus full of screaming passengers, killing three women, two children, one man and the bus driver.

Meanwhile, on the barracks grounds, parents were getting their children ready for school, wrapping chapatis, polishing shoes and knotting ties. The three men strolled into the compound and started shooting and lobbing hand grenades. They trotted from house to house, murdering mothers and their children. Indian troops arrived within minutes but it would take over three hours to hunt the terrorists down. By the time the army had finished the intruders off, 23 people were dead, including 11 children.

Some hitherto unknown militant group claimed responsibility and India immediately blamed its neighbor, announcing that a chocolate bar carried by one of the terrorists was made in Pakistan. Islamabad, as usual, denounced the carnage, denied complicity and added that India had no real proof. It's a familiar pattern. Gruesome attacks against Indian targetsââ¬âfrequently suicidalââ¬âhave been a regular feature of the Kashmir imbroglio for the past decade.

But the attack in Jammu was no ordinary strike at India. It occurred the very day that a senior U.S. diplomat, Assistant Secretary of State Christina Rocca, was in New Delhi trying to arm-twist some peace. After the attack on Parliament in December, India went to war footing, demanding that Pakistan crack down on its anti-India terroristsââ¬âalmost all of them working to stir trouble in Kashmirââ¬âand demanded the extradition to India of 20 named terrorist suspects. Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf ordered some militants arrestedââ¬âmany of whom have been subsequently releasedââ¬âand refused to extradite any of those on India's list. That's why the troops are still eyeballing each other on a searingly hot border. India has signaled for months it might launch its own strike on Pakistan, probably in Kashmir. The most likely impetus: another outrageous, high profile terrorist strike.

In fact, India probably won't be goaded into military action by a well-timed terrorist attack. State elections are due by October in Kashmir, and New Delhi has hopes that they will take some steam out of the indigenous militancy. Many of the candidates are former insurgents won over by the government. (India's time-honored method of defusing insurgencies is to woo tired separatists to run for election, after which they can get their hands on loosely-watched government coffers.)

Once the elections are over, however, all bets are off as to whether the peace will hold. Pakistani-based separatists will filter across the Line of Control all through the summer. Then the attacks, ambushes and suicide missions will start. The talk in New Delhi these days is of some kind of war in September or October. It's pretty clear where it will start: Kashmir.

After 13 years of such violent tides, Kashmir's children are all over the mapââ¬âsome literally, others in the myriad ways they view their home and the possible futures it holds for them. Moulvi Imran Mushtaq decided to stay. He was ambitious, with dreams of becoming a doctor, and worked hard to win admission to Srinagar's Government Medical College. Violence, however, shut down his school for long periods; Moulvi's four and a half year curriculum took seven years to complete. "It was full of risk sending him to college," says his father Moulvi Mushtaq Ahmed. Avoiding an ambush was one challenge. He also had to be wary of being picked up by Indian troops as a suspected militant and tossed in one of the valley's detention/torture centers. Imran, 27, avoided both fates and actually got a job at the state health department.

Muhammed Amin Butt, a Srinagar lawyer, says he could barely afford to send his son Omar away for education. However, the worried attorney believes he really had no choice. "Kashmir was politically too hot and everybody's life was at peril. Secondly, the educational system had been cast to the dogs." Omar went to Kolhapur and earned an engineering degree and then came home to Srinagar, but has failed to find work. (Virtually the only employers in Kashmir are the state government, the despised police force and the carpet weavers and handicraft factories.) Omar is wondering whether to leave home againââ¬âthe U.S.? the Middle East?ââ¬âand his mother Hafiza is encouraging him, still frightened at tales of revenge killings and boys being tossed into Indian jails. "Kashmir is still not a place worth living," she says, "particularly for boys of his age."

Kashmiris are a people in-between, stuck in the vise of a vicious, intractable geopolitical mess, and even when they leave, their fate sometimes follows. Syed Shahnaaz Qadiri decided to move out of Kashmir four years ago. His choice was to go to another state, where the school years start and end on time and students aren't afraid to walk to class. But Qadiri is a Kashmiri Muslim. He chose a college near Ahmadabad, the main city in the western Indian state of Gujarat. Two months ago, a mob of Muslims torched a train carriage near Ahmadabad, killing 58 Hindus. In the aftermath, nearly a thousand Muslims have been killed in reprisals that fail to simmer down. Qadiri's parents are spending a fortune trying to keep in touch with their son by phone, hoping he won't be the next victim. Qadiri had the luck of the Kashmiris: he found the only other place on the subcontinent as dangerous as his own hometown. With reporting by Reported by Meenakshi Ganguly and Yusuf Jameel/Srinagar

Source: Time Magzine

Sheikh Zahoor Ahmed and his wife Dilshad sent their son abroad to escape Kashmir's cycle of violence

Monday, May. 20, 2002

Procreation implies optimism. Mothers and fathers must believe that society will provide a haven, an environment in which their children will thrive. What does it say, then, if parents no longer have that faith? If rather than raise their children themselves, parents would send their beloved to far-flung corners of the world, anywhere, really, to escape the carnage of Kashmir?

Dilshada and Zahoor Ahmed Sheikh faced that bleak reality when their son Khalid was 16. Khalid was looking up to some dangerous role models: a few older friends who had gone across the border to Pakistan to join up with the anti-India insurgency raging in Kashmir. He developed a schoolboy enthusiasm for AK-47s. Then Khalid announced there was no point studying because, in his words, "Everyone is going to die anyway." The couple had to make a decision. "We summoned up our courage," says mother Dilshada, "and sent him away."

It was the best thing that could have happened to a young Kashmiri in the 1990s. Ten years later, Khalid has a master's in business administration from Ohio University and is planning to go back to the U.S. for an additional degree, this one in finance. His friends who stayed behind to study medicine or law don't have a hope of practicing their professions: there are no jobs in Kashmir. Of his ten closest schoolmates, four joined the militancyââ¬âat least one died in actionââ¬âand others left town. When Khalid returns for holidays, he finds Kashmir stiflingly oppressive. Last month, he and his 49-year-old father were ordered out of their car by Indian soldiers for a security check. "They were so rude, I couldn't believe my father was being all soft and pleading, giving them explanations. But he told me later: 'This is the way things are here.'"

To call Kashmir the subcontinent's West Bank or Gaza Strip would be a stretch. The Kashmir Valley, the heart and soul of the territory, is one of the earth's lovelier places. Many Kashmiris are poor, but no one lives in 50-year-old refugee settlements. Unlike the Palestinians, they have a homeland.

But it's a homeland more and more are abandoning because Kashmir is where the tension between India and Pakistan always surfaces. Kashmir is the biggest bit of unfinished business from the partition of the subcontinent 53 years ago. Pakistan still believes it shouldn't have gone to India, the Indians will probably never let it go, and both sides are more than willing to fight over itââ¬âpotentially with atomic warheads. Two of the three wars fought between the two countries started off in Kashmir. Since the beginning of the year, both have mobilized their armies along their common border and kept them at high alert, a state of war readiness prompted by a December terrorist attack intended to blow up the Parliament building in New Delhi. And last week, 30 people were killed by some fidayeen, a suicide squad that sneaked in from Pakistan, setting off a fresh round of accusations, the possible expulsion of Pakistan's ambassador from New Delhi, and some heavy shelling at the Line of Control, the de facto border that splits Kashmir.

Stuck in the middle, Kashmiris have either stolidly borne up, joined the separatist militants, or been forced to find a decent life far away from family, the mother tongue and the mountains, orchards and idyllic lakes. "The militancy turned out to be a blessing for me," says Khalid. "If there had been no violence, I would have studied at home and joined the family business." Khalid's family has a substantial textile and carpet business. They could afford to buy their son freedom.

Most other Kashmiris have no such luck. Their home is the disputed prize in what may be the most dangerous conflict on earth. In the early months of 1999, Pakistani soldiers took control of a mountain ridge on the Indian side of the Line of Control. In the spring, when they were discovered, that sparked the Kargil War, named for the region where it was fought. Both sides had tested nukes a few months earlier; last week in Washington, Bruce Riedel, senior director at the National Security Council, revealed that the Pakistani army, without informing its own government, had mobilized its nuclear arsenal at the height of the conflict. Former U.S. President Clinton persuaded then-Pakistani Prime Minister Mian Nawaz Sharif to withdraw his forces, ending what appears to be one of the closest brushes with nuclear war since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

Last week, the countries went back to the brink. Shortly before dawn on Tuesday, three men in army uniforms, who were later identified as Pakistani citizens, boarded a Himachal Roadways passenger bus on its way to Jammu, winter capital of India's Jammu and Kashmir state. On board for 15 minutes, the men asked to be dropped off near an army barracks. After the bus had stopped, the men ordered the sleepy passengers to the back of the vehicle and opened fire. They tossed a grenade into the bus full of screaming passengers, killing three women, two children, one man and the bus driver.

Meanwhile, on the barracks grounds, parents were getting their children ready for school, wrapping chapatis, polishing shoes and knotting ties. The three men strolled into the compound and started shooting and lobbing hand grenades. They trotted from house to house, murdering mothers and their children. Indian troops arrived within minutes but it would take over three hours to hunt the terrorists down. By the time the army had finished the intruders off, 23 people were dead, including 11 children.

Some hitherto unknown militant group claimed responsibility and India immediately blamed its neighbor, announcing that a chocolate bar carried by one of the terrorists was made in Pakistan. Islamabad, as usual, denounced the carnage, denied complicity and added that India had no real proof. It's a familiar pattern. Gruesome attacks against Indian targetsââ¬âfrequently suicidalââ¬âhave been a regular feature of the Kashmir imbroglio for the past decade.

But the attack in Jammu was no ordinary strike at India. It occurred the very day that a senior U.S. diplomat, Assistant Secretary of State Christina Rocca, was in New Delhi trying to arm-twist some peace. After the attack on Parliament in December, India went to war footing, demanding that Pakistan crack down on its anti-India terroristsââ¬âalmost all of them working to stir trouble in Kashmirââ¬âand demanded the extradition to India of 20 named terrorist suspects. Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf ordered some militants arrestedââ¬âmany of whom have been subsequently releasedââ¬âand refused to extradite any of those on India's list. That's why the troops are still eyeballing each other on a searingly hot border. India has signaled for months it might launch its own strike on Pakistan, probably in Kashmir. The most likely impetus: another outrageous, high profile terrorist strike.

In fact, India probably won't be goaded into military action by a well-timed terrorist attack. State elections are due by October in Kashmir, and New Delhi has hopes that they will take some steam out of the indigenous militancy. Many of the candidates are former insurgents won over by the government. (India's time-honored method of defusing insurgencies is to woo tired separatists to run for election, after which they can get their hands on loosely-watched government coffers.)

Once the elections are over, however, all bets are off as to whether the peace will hold. Pakistani-based separatists will filter across the Line of Control all through the summer. Then the attacks, ambushes and suicide missions will start. The talk in New Delhi these days is of some kind of war in September or October. It's pretty clear where it will start: Kashmir.

After 13 years of such violent tides, Kashmir's children are all over the mapââ¬âsome literally, others in the myriad ways they view their home and the possible futures it holds for them. Moulvi Imran Mushtaq decided to stay. He was ambitious, with dreams of becoming a doctor, and worked hard to win admission to Srinagar's Government Medical College. Violence, however, shut down his school for long periods; Moulvi's four and a half year curriculum took seven years to complete. "It was full of risk sending him to college," says his father Moulvi Mushtaq Ahmed. Avoiding an ambush was one challenge. He also had to be wary of being picked up by Indian troops as a suspected militant and tossed in one of the valley's detention/torture centers. Imran, 27, avoided both fates and actually got a job at the state health department.

Muhammed Amin Butt, a Srinagar lawyer, says he could barely afford to send his son Omar away for education. However, the worried attorney believes he really had no choice. "Kashmir was politically too hot and everybody's life was at peril. Secondly, the educational system had been cast to the dogs." Omar went to Kolhapur and earned an engineering degree and then came home to Srinagar, but has failed to find work. (Virtually the only employers in Kashmir are the state government, the despised police force and the carpet weavers and handicraft factories.) Omar is wondering whether to leave home againââ¬âthe U.S.? the Middle East?ââ¬âand his mother Hafiza is encouraging him, still frightened at tales of revenge killings and boys being tossed into Indian jails. "Kashmir is still not a place worth living," she says, "particularly for boys of his age."

Kashmiris are a people in-between, stuck in the vise of a vicious, intractable geopolitical mess, and even when they leave, their fate sometimes follows. Syed Shahnaaz Qadiri decided to move out of Kashmir four years ago. His choice was to go to another state, where the school years start and end on time and students aren't afraid to walk to class. But Qadiri is a Kashmiri Muslim. He chose a college near Ahmadabad, the main city in the western Indian state of Gujarat. Two months ago, a mob of Muslims torched a train carriage near Ahmadabad, killing 58 Hindus. In the aftermath, nearly a thousand Muslims have been killed in reprisals that fail to simmer down. Qadiri's parents are spending a fortune trying to keep in touch with their son by phone, hoping he won't be the next victim. Qadiri had the luck of the Kashmiris: he found the only other place on the subcontinent as dangerous as his own hometown. With reporting by Reported by Meenakshi Ganguly and Yusuf Jameel/Srinagar

Source: Time Magzine