walterbibikow

BANNED

- Joined

- Nov 12, 2022

- Messages

- 959

- Reaction score

- -4

- Country

- Location

Bloomberg Economics expects the nation's per capita income to pull even with some developed countries in that span, putting Modi's goal within reach

Prime Minister Narendra Modi | Photo: Bloomberg

India’s economic transformation is kicking into high gear.

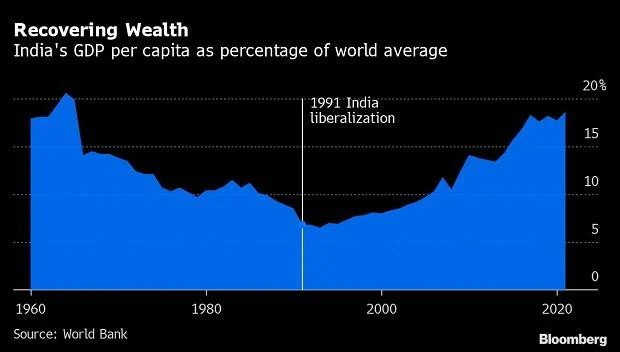

Global manufacturers are looking beyond China, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi stepping up to seize the moment. The government is spending nearly 20% of its budget this fiscal year on capital investments, the most in at least a decade.

Modi is closer than any predecessor to being able to claim that the nation — which may have just passed China as the world’s most populous — is finally meeting its economic potential. To get there, he’ll have to wrestle with the drawbacks of its exceptional scale: the remnants of the red tape and corruption that has slowed India’s rise, and the stark inequality that defines the democracy of 1.4 billion people.

“India is on the cusp of huge change,” said Nandan Nilekani, a founder of Infosys Ltd., one of the nation’s largest technology services companies. India has quickly created capacity to support tens of thousands of startups, a few billion smartphones and data rates that rank among the lowest in the world, he said

The Infosys campus in Bengaluru in December. Photographer: Aparna Jayakumar/Bloomberg

US-China rivalry is providing a tailwind. India and Vietnam will be the big beneficiaries as companies move toward a “China-plus-one” strategy, supply-chain analysts say. Apple Inc.’s three key Taiwanese suppliers have won incentives from Modi’s government to boost smartphone production and exports. Shipments more than doubled to top $3.5 billion of iPhones from April through December.

As powerhouses from China to Germany contend with slowing growth, the stakes are rising to find another nation equipped to propel the global economy. Morgan Stanley predicts that India will drive a fifth of world expansion this decade, positioning the nation as one of only three that can generate more than $400 billion in annual output growth.

The thesis is reflected in global equity markets, with India’s Sensex index trading last quarter at the highest in a decade versus the S&P 500. Relative to other emerging markets, Indian stocks have never been higher.

President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Narendra Modi during the G20 Summit in Nusa Dua, Indonesia in November. Photographer: Leon Neal/Getty Images Europe

“People are looking at which other place over the next decade is going to be a great place to put capital,” Nilekani said. “I haven’t seen this kind of interest in India for 15 years.”

Of course, Modi’s manufacturing aspirations are not new. His “Make in India” campaign kicked off in 2014, seeking to emulate China and the tigers of East Asia — from Singapore to South Korea and Taiwan — that climbed into the ranks of rich economies by filling factories with workers making products the world wanted to buy.

Boosting manufacturing to 25% of GDP, a key metric for the program, has proven elusive. The ratio rose to 17.4% in 2020 compared with 15.3% in 2000, according to data from McKinsey. Vietnam’s factory sector more than doubled its share of GDP during the same period.

But as this year’s president of the Group of 20 nations, India has momentum. An external strategy built on multiple alliances and unapologetic self-interest has seen the nation boost purchases of Russian oil by 33 times, ignoring pressure from Washington. There are even some signs of pragmatism when it comes to the tense relationship with neighboring China — more than a dozen of Apple’s Chinese suppliers are receiving initial clearance from New Delhi to expand operations, underpinning the tech giant’s efforts to divert production to India.

In a multipolar world, India’s embrace of a middle path has bolstered its image as a nation “with which everyone is interested in having a good relationship,” said Kenneth Juster, a former US ambassador to India.

“India is positioning itself, and using its presidency of the G-20 to do so, as a bridge between east and west, and north and south,” he said. “A lot of companies feel that given its size, given its young population, given its inevitable force in international affairs, India is a place where they should be.”

In an August speech commemorating 75 years since India’s independence, Modi urged the nation to settle for nothing less than to “dominate the world.”

“We must resolve to make India a developed nation in the next 25 years,” he said at the Red Fort in New Delhi, occasionally swatting the air with clenched fists. Helicopters showered the crowd with flower petals before he spoke

Bloomberg Economics expects the nation’s per capita income to pull even with some developed countries in that span, putting Modi’s goal within reach. Potential GDP growth will gradually peak at about 8.5% early next decade, propelled by corporate tax cuts, incentives for manufacturers and privatization of public assets, according to BE. The Centre for Economics and Business Research predicts India to become a $10 trillion economy by 2035.

Battling Bureaucracy

To meet his target, Modi will have to overcome the legacy of India’s early years as an independent nation, which included decades of squandered economic opportunity.

After Britain’s partition of the subcontinent in 1947 and the religious violence that followed, India turned inward. By the 1970s, much of the economy was nationalized and a formidable bureaucracy shut out the world. A labyrinthine system called the “License Raj” dictated everything from car models to what types of bread were allowed in stores.

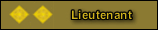

In 1991, a balance of payments crisis forced change. Facing plunging foreign exchange reserves and pressure from the International Monetary Fund, then-Finance Minister Manmohan Singh endorsed devaluing the rupee and opening up to foreign investment.

The reforms were a hard sell. But by the end of the decade, changes to India’s economic landscape were undeniable. GDP close to doubled. International brands from McDonald’s to Microsoft offered new choices. In the 2000s, India notched several years of growth near 8%.

When Modi rose to power in 2014, campaigning on “minimum government, maximum governance,” voters saw an opportunity to build on liberalization, hoping for “Ronald Reagan on a white horse,” as a prominent economist put it.

India’s new prime minister, the son of a tea seller, promised to clear the remaining cobwebs from the License Raj, including a culture of paying bribes for access to public services. Modi styled himself as a political outsider with managerial panache, poised to apply his experience running Gujarat, one of the nation’s most industrialized states, to propel India toward top-down development, à la China.

He can claim significant progress, especially on infrastructure. Since Modi's election win in 2014, India’s national highway network grew more than 50% longer, domestic air passengers roughly doubled and a vast biometric system helped several hundred million people open bank accounts for the first time.

Among Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party’s most heralded achievements has been forging a single economic zone from India’s overlapping federal and state taxes, perhaps the most consequential measure since 1991. Tax revenue collection hit a high last year, jumping 34% from the previous year. The government will lay out its budget for the next fiscal year on Feb. 1.

Streamlining India’s economy has “brought a lot more transparency in the system,” said Adar Poonawalla, the chief executive of the Serum Institute of India, one of the world’s largest vaccine manufacturers. “Look at collection now. The government is getting double or triple what they were getting in the previous regime.”

The reception was chillier for Modi’s 2016 ban on nearly all local-currency banknotes to fight corruption and tax avoidance. The shock announcement devastated Indians working for cash daily wages. And Modi struck another speed bump when he took his liberalization campaign to the agricultural sector, which makes up about a fifth of the economy. Sweeping reforms were abandoned in 2021 after mass protests saw thousands of farmers camping on the outskirts of the capital for months.

Gurcharan Das, an author and former chief executive of Procter & Gamble India, said Modi still has much to prove if he wants to transform India in the way that Margaret Thatcher revolutionized Britain. Part of the challenge is that Indian voters — many of whom still live on less than a few dollars a day — gravitate to tangible political pledges like free electricity, rather than abstract policies to spur investment.

“In India, nobody has sold the reforms, so people believe they’ll make the rich richer and the poor poorer,” Das said.

But Sanjeev Sanyal, an economic advisor to Modi’s administration, projected confidence, characterizing these issues as teething troubles that would afflict any young nation.

Boosting supply side productivity, enabling creative destruction and continuing to reduce absolute poverty are among India’s objectives for the next 25 years, he said.

“We are finally getting rid of the bureaucratic shackles in our heads,” Sanyal said.

Rising Inequality

India’s population stood at 1.417 billion at the end of last year, according to estimates from the World Population Review, about 5 million more than China has reported. The United Nations expects India to reach the milestone later this year. Half of India’s people are under the age of 30, while China’s citizens are aging rapidly, and its population shrank in 2022 for the first time since the final year of the Great Famine in the 1960s.

Among other notable differences: India’s middle class remains significantly smaller. The share of the middle class in the total population rose from 14 per cent in 2004-05 to 31 per cent in 2021-22. Fully capturing the nation’s demographic dividend — perhaps its biggest advantage compared to bigger economies — will require broader wealth creation that resolves high unemployment among women, minorities and young people.

“If we do not take care of inequality, we can’t get very far with growth,” said Duvvuri Subbarao, a former governor of the Reserve Bank of India.

Nowhere else is the super wealthy growing faster than in India, drawing comparisons to the heady times of America’s Gilded Age. Since 1995, the wealth gap between the top 1% and bottom 50% has soared about three times more than the equivalent metric for the US.

A new class of entrepreneurs is creating more unicorns — unlisted companies worth at least $1 billion — than any other nation apart from the US and China. Their growing success is propelling property prices in Mumbai and Bangalore hotspots, while encouraging firms from UBS Group AG to Deutsche Bank AG to hire more private bankers.

Yet by one estimate, female labor force participation fell to 9% by 2020-21, in part because of the pandemic. Closing the gap between men and women — 58 percentage points — could expand India’s GDP by more than 30% by 2050, an analysis from Bloomberg Economics found.

Factory Dreams

The Viraj Exports factory in October. Photographer: Anindito Mukherjee/Bloomberg

Sanyal, the economic advisor to Modi’s administration, said the government is working to create opportunities for all Indians and it’s unfair to hold one leader responsible for long-running challenges.

Raising manufacturing to a quarter of GDP — and the jobs bounty that would come along with it — remains a top priority. While India’s contribution to global trade is less than 2%, merchandise exports exceeded a record $400 billion last fiscal year.

To compete with China, the government is providing more than $24 billion in incentives over the next few years in more than a dozen industries. Some of the money will support the production of mobile phone handsets by Wistron Corp. and Samsung Electronics Co.; semi-conductors by Hon Hai Precision Industry Co.; and solar panels by Reliance Industries Ltd. In coming months the program will be extended to manufacturers of electrolyzers and other equipment needed to make green hydrogen. The next step is boosting production beyond the world’s manufacturing behemoths.

Shiv Bhargava, the founder of Viraj Exports, a mid-sized garment exporter, said building scale in India can be difficult. At his factory in the industrial city of Noida, Bhargava weaved between sewing stations where workers stitched clothing bound for Zara. He has about 1,000 staff in the country, but says he’d have more if it weren’t for relatively restrictive labor laws. Modi has sought to streamline the rules, sparking fierce opposition from some state governments.

“Compared to Bangladesh, our costs are 40% to 50% higher,” Bhargava said. “When the economy of a country goes up, then labor has the option to have better options.”

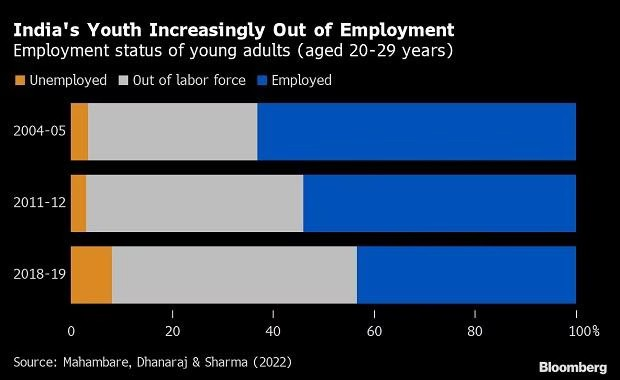

Some younger Indians, aspiring to white collar work, are deferring employment rather than laboring in a factory. About half of potential workers under the age of 30 aren’t even looking for jobs.

The numbers are also explained by changing employment patterns, especially in rural areas, home to much of India’s population. In Haryana, a key farming state, the evaporation of agricultural jobs has forced workers to migrate from towns to urban centers.

Perched on a rope cot, Kusum, a young woman who lost a teaching position during the pandemic, said liberalization has benefited the village of Mundakhera. Her family can now afford a washing machine and motorcycle. Every morning, she uses her smartphone to scan Google for employment opportunities and catch up on current events.

But as farming declines, she said, India has to move faster to equip her generation with marketable skills in a more globalized economy. Quality jobs are now scarcer in Mundakhera, where tidy brick homes surround a pond speckled with algae.

“Our education is not skill-based and the private sector needs that,” she said

Building India’s Future

Even with those obstacles, optimism pervades India’s business elite. Entrepreneurs are eager to capitalize on a stronger tolerance for risk-taking, higher consumer spending and a vibrant ecosystem for digital startups.

In Mumbai, the airy headquarters of Nykaa is abuzz as young employees film content with makeup kits. The business, India’s top e-commerce site for beauty products, has a fervent following among Bollywood stars and more than 100 brick-and-mortar stores.

Actor Priyanka Chopra Jonas outside o the Nykaa Luxe store in Mumbai in November. Photographer: Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg

Falguni Nayar, a former banker who started Nykaa with her daughter in 2012, said India has cleared “banana skins” that entrepreneurs used to slip on. The industry benefitted from changes like the easing of taxes on premium products, she said. In 2021, Nykaa raised 53.5 billion rupees (about $660 million) in a stellar initial public offering, helping to make Nayar the country’s richest self-made woman.

“Before we know it, we’ll be the third largest economy in the world,” she said. Nayar’s often asked if consumption is stronger in cities than in rural areas. “Not anymore,” she said. In many towns, “if earlier we used to see fans, now they’ll have air conditioners and refrigerators.”

Modi’s popularity remains robust, giving him a platform to enact change that many world leaders would envy. Polls consistently peg the prime minister’s approval rating above 70%.

This month Modi urged members of his ruling party to reach out to Muslims and other religious minorities, a rare move to tone down sectarian tensions as he prepares to host the G-20 summit. With national elections due in 2024, the question on the horizon is the extent to which economic ambition will shape Modi’s agenda and how he expends his political capital.

“We’re optimistic,” said Poonawalla, the chief executive of the Serum Institute of India. “Despite the disruption in supply chains and oil prices and inflation and the war crisis, India, fundamentally, is doing very well.”

wap.business-standard.com

wap.business-standard.com

Prime Minister Narendra Modi | Photo: Bloomberg

India’s economic transformation is kicking into high gear.

Global manufacturers are looking beyond China, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi stepping up to seize the moment. The government is spending nearly 20% of its budget this fiscal year on capital investments, the most in at least a decade.

Modi is closer than any predecessor to being able to claim that the nation — which may have just passed China as the world’s most populous — is finally meeting its economic potential. To get there, he’ll have to wrestle with the drawbacks of its exceptional scale: the remnants of the red tape and corruption that has slowed India’s rise, and the stark inequality that defines the democracy of 1.4 billion people.

“India is on the cusp of huge change,” said Nandan Nilekani, a founder of Infosys Ltd., one of the nation’s largest technology services companies. India has quickly created capacity to support tens of thousands of startups, a few billion smartphones and data rates that rank among the lowest in the world, he said

The Infosys campus in Bengaluru in December. Photographer: Aparna Jayakumar/Bloomberg

US-China rivalry is providing a tailwind. India and Vietnam will be the big beneficiaries as companies move toward a “China-plus-one” strategy, supply-chain analysts say. Apple Inc.’s three key Taiwanese suppliers have won incentives from Modi’s government to boost smartphone production and exports. Shipments more than doubled to top $3.5 billion of iPhones from April through December.

As powerhouses from China to Germany contend with slowing growth, the stakes are rising to find another nation equipped to propel the global economy. Morgan Stanley predicts that India will drive a fifth of world expansion this decade, positioning the nation as one of only three that can generate more than $400 billion in annual output growth.

The thesis is reflected in global equity markets, with India’s Sensex index trading last quarter at the highest in a decade versus the S&P 500. Relative to other emerging markets, Indian stocks have never been higher.

President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Narendra Modi during the G20 Summit in Nusa Dua, Indonesia in November. Photographer: Leon Neal/Getty Images Europe

“People are looking at which other place over the next decade is going to be a great place to put capital,” Nilekani said. “I haven’t seen this kind of interest in India for 15 years.”

Of course, Modi’s manufacturing aspirations are not new. His “Make in India” campaign kicked off in 2014, seeking to emulate China and the tigers of East Asia — from Singapore to South Korea and Taiwan — that climbed into the ranks of rich economies by filling factories with workers making products the world wanted to buy.

Boosting manufacturing to 25% of GDP, a key metric for the program, has proven elusive. The ratio rose to 17.4% in 2020 compared with 15.3% in 2000, according to data from McKinsey. Vietnam’s factory sector more than doubled its share of GDP during the same period.

But as this year’s president of the Group of 20 nations, India has momentum. An external strategy built on multiple alliances and unapologetic self-interest has seen the nation boost purchases of Russian oil by 33 times, ignoring pressure from Washington. There are even some signs of pragmatism when it comes to the tense relationship with neighboring China — more than a dozen of Apple’s Chinese suppliers are receiving initial clearance from New Delhi to expand operations, underpinning the tech giant’s efforts to divert production to India.

In a multipolar world, India’s embrace of a middle path has bolstered its image as a nation “with which everyone is interested in having a good relationship,” said Kenneth Juster, a former US ambassador to India.

“India is positioning itself, and using its presidency of the G-20 to do so, as a bridge between east and west, and north and south,” he said. “A lot of companies feel that given its size, given its young population, given its inevitable force in international affairs, India is a place where they should be.”

In an August speech commemorating 75 years since India’s independence, Modi urged the nation to settle for nothing less than to “dominate the world.”

“We must resolve to make India a developed nation in the next 25 years,” he said at the Red Fort in New Delhi, occasionally swatting the air with clenched fists. Helicopters showered the crowd with flower petals before he spoke

Bloomberg Economics expects the nation’s per capita income to pull even with some developed countries in that span, putting Modi’s goal within reach. Potential GDP growth will gradually peak at about 8.5% early next decade, propelled by corporate tax cuts, incentives for manufacturers and privatization of public assets, according to BE. The Centre for Economics and Business Research predicts India to become a $10 trillion economy by 2035.

Battling Bureaucracy

To meet his target, Modi will have to overcome the legacy of India’s early years as an independent nation, which included decades of squandered economic opportunity.

After Britain’s partition of the subcontinent in 1947 and the religious violence that followed, India turned inward. By the 1970s, much of the economy was nationalized and a formidable bureaucracy shut out the world. A labyrinthine system called the “License Raj” dictated everything from car models to what types of bread were allowed in stores.

In 1991, a balance of payments crisis forced change. Facing plunging foreign exchange reserves and pressure from the International Monetary Fund, then-Finance Minister Manmohan Singh endorsed devaluing the rupee and opening up to foreign investment.

The reforms were a hard sell. But by the end of the decade, changes to India’s economic landscape were undeniable. GDP close to doubled. International brands from McDonald’s to Microsoft offered new choices. In the 2000s, India notched several years of growth near 8%.

When Modi rose to power in 2014, campaigning on “minimum government, maximum governance,” voters saw an opportunity to build on liberalization, hoping for “Ronald Reagan on a white horse,” as a prominent economist put it.

India’s new prime minister, the son of a tea seller, promised to clear the remaining cobwebs from the License Raj, including a culture of paying bribes for access to public services. Modi styled himself as a political outsider with managerial panache, poised to apply his experience running Gujarat, one of the nation’s most industrialized states, to propel India toward top-down development, à la China.

He can claim significant progress, especially on infrastructure. Since Modi's election win in 2014, India’s national highway network grew more than 50% longer, domestic air passengers roughly doubled and a vast biometric system helped several hundred million people open bank accounts for the first time.

Among Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party’s most heralded achievements has been forging a single economic zone from India’s overlapping federal and state taxes, perhaps the most consequential measure since 1991. Tax revenue collection hit a high last year, jumping 34% from the previous year. The government will lay out its budget for the next fiscal year on Feb. 1.

Streamlining India’s economy has “brought a lot more transparency in the system,” said Adar Poonawalla, the chief executive of the Serum Institute of India, one of the world’s largest vaccine manufacturers. “Look at collection now. The government is getting double or triple what they were getting in the previous regime.”

The reception was chillier for Modi’s 2016 ban on nearly all local-currency banknotes to fight corruption and tax avoidance. The shock announcement devastated Indians working for cash daily wages. And Modi struck another speed bump when he took his liberalization campaign to the agricultural sector, which makes up about a fifth of the economy. Sweeping reforms were abandoned in 2021 after mass protests saw thousands of farmers camping on the outskirts of the capital for months.

Gurcharan Das, an author and former chief executive of Procter & Gamble India, said Modi still has much to prove if he wants to transform India in the way that Margaret Thatcher revolutionized Britain. Part of the challenge is that Indian voters — many of whom still live on less than a few dollars a day — gravitate to tangible political pledges like free electricity, rather than abstract policies to spur investment.

“In India, nobody has sold the reforms, so people believe they’ll make the rich richer and the poor poorer,” Das said.

But Sanjeev Sanyal, an economic advisor to Modi’s administration, projected confidence, characterizing these issues as teething troubles that would afflict any young nation.

Boosting supply side productivity, enabling creative destruction and continuing to reduce absolute poverty are among India’s objectives for the next 25 years, he said.

“We are finally getting rid of the bureaucratic shackles in our heads,” Sanyal said.

Rising Inequality

India’s population stood at 1.417 billion at the end of last year, according to estimates from the World Population Review, about 5 million more than China has reported. The United Nations expects India to reach the milestone later this year. Half of India’s people are under the age of 30, while China’s citizens are aging rapidly, and its population shrank in 2022 for the first time since the final year of the Great Famine in the 1960s.

Among other notable differences: India’s middle class remains significantly smaller. The share of the middle class in the total population rose from 14 per cent in 2004-05 to 31 per cent in 2021-22. Fully capturing the nation’s demographic dividend — perhaps its biggest advantage compared to bigger economies — will require broader wealth creation that resolves high unemployment among women, minorities and young people.

“If we do not take care of inequality, we can’t get very far with growth,” said Duvvuri Subbarao, a former governor of the Reserve Bank of India.

Nowhere else is the super wealthy growing faster than in India, drawing comparisons to the heady times of America’s Gilded Age. Since 1995, the wealth gap between the top 1% and bottom 50% has soared about three times more than the equivalent metric for the US.

A new class of entrepreneurs is creating more unicorns — unlisted companies worth at least $1 billion — than any other nation apart from the US and China. Their growing success is propelling property prices in Mumbai and Bangalore hotspots, while encouraging firms from UBS Group AG to Deutsche Bank AG to hire more private bankers.

Yet by one estimate, female labor force participation fell to 9% by 2020-21, in part because of the pandemic. Closing the gap between men and women — 58 percentage points — could expand India’s GDP by more than 30% by 2050, an analysis from Bloomberg Economics found.

Factory Dreams

The Viraj Exports factory in October. Photographer: Anindito Mukherjee/Bloomberg

Sanyal, the economic advisor to Modi’s administration, said the government is working to create opportunities for all Indians and it’s unfair to hold one leader responsible for long-running challenges.

Raising manufacturing to a quarter of GDP — and the jobs bounty that would come along with it — remains a top priority. While India’s contribution to global trade is less than 2%, merchandise exports exceeded a record $400 billion last fiscal year.

To compete with China, the government is providing more than $24 billion in incentives over the next few years in more than a dozen industries. Some of the money will support the production of mobile phone handsets by Wistron Corp. and Samsung Electronics Co.; semi-conductors by Hon Hai Precision Industry Co.; and solar panels by Reliance Industries Ltd. In coming months the program will be extended to manufacturers of electrolyzers and other equipment needed to make green hydrogen. The next step is boosting production beyond the world’s manufacturing behemoths.

Shiv Bhargava, the founder of Viraj Exports, a mid-sized garment exporter, said building scale in India can be difficult. At his factory in the industrial city of Noida, Bhargava weaved between sewing stations where workers stitched clothing bound for Zara. He has about 1,000 staff in the country, but says he’d have more if it weren’t for relatively restrictive labor laws. Modi has sought to streamline the rules, sparking fierce opposition from some state governments.

“Compared to Bangladesh, our costs are 40% to 50% higher,” Bhargava said. “When the economy of a country goes up, then labor has the option to have better options.”

Some younger Indians, aspiring to white collar work, are deferring employment rather than laboring in a factory. About half of potential workers under the age of 30 aren’t even looking for jobs.

The numbers are also explained by changing employment patterns, especially in rural areas, home to much of India’s population. In Haryana, a key farming state, the evaporation of agricultural jobs has forced workers to migrate from towns to urban centers.

Perched on a rope cot, Kusum, a young woman who lost a teaching position during the pandemic, said liberalization has benefited the village of Mundakhera. Her family can now afford a washing machine and motorcycle. Every morning, she uses her smartphone to scan Google for employment opportunities and catch up on current events.

But as farming declines, she said, India has to move faster to equip her generation with marketable skills in a more globalized economy. Quality jobs are now scarcer in Mundakhera, where tidy brick homes surround a pond speckled with algae.

“Our education is not skill-based and the private sector needs that,” she said

Building India’s Future

Even with those obstacles, optimism pervades India’s business elite. Entrepreneurs are eager to capitalize on a stronger tolerance for risk-taking, higher consumer spending and a vibrant ecosystem for digital startups.

In Mumbai, the airy headquarters of Nykaa is abuzz as young employees film content with makeup kits. The business, India’s top e-commerce site for beauty products, has a fervent following among Bollywood stars and more than 100 brick-and-mortar stores.

Actor Priyanka Chopra Jonas outside o the Nykaa Luxe store in Mumbai in November. Photographer: Dhiraj Singh/Bloomberg

Falguni Nayar, a former banker who started Nykaa with her daughter in 2012, said India has cleared “banana skins” that entrepreneurs used to slip on. The industry benefitted from changes like the easing of taxes on premium products, she said. In 2021, Nykaa raised 53.5 billion rupees (about $660 million) in a stellar initial public offering, helping to make Nayar the country’s richest self-made woman.

“Before we know it, we’ll be the third largest economy in the world,” she said. Nayar’s often asked if consumption is stronger in cities than in rural areas. “Not anymore,” she said. In many towns, “if earlier we used to see fans, now they’ll have air conditioners and refrigerators.”

Modi’s popularity remains robust, giving him a platform to enact change that many world leaders would envy. Polls consistently peg the prime minister’s approval rating above 70%.

This month Modi urged members of his ruling party to reach out to Muslims and other religious minorities, a rare move to tone down sectarian tensions as he prepares to host the G-20 summit. With national elections due in 2024, the question on the horizon is the extent to which economic ambition will shape Modi’s agenda and how he expends his political capital.

“We’re optimistic,” said Poonawalla, the chief executive of the Serum Institute of India. “Despite the disruption in supply chains and oil prices and inflation and the war crisis, India, fundamentally, is doing very well.”

India's 1.4 bn population could become world economy's new growth engine

Bloomberg Economics expects the nation's per capita income to pull even with some developed countries in that span, putting Modi's goal within reach