beijingwalker

ELITE MEMBER

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2011

- Messages

- 65,191

- Reaction score

- -55

- Country

- Location

Life expectancy in U.S. is falling amid surges in chronic illness

Oct. 3 at 6:00 a.m.

The United States is failing at a fundamental mission — keeping people alive.

After decades of progress, life expectancy — long regarded as a singular benchmark of a nation’s success — peaked in 2014 at 78.9 years, then drifted downward even before the coronavirus pandemic. Among wealthy nations, the United States in recent decades went from the middle of the pack to being an outlier. And it continues to fall further and further behind.

A year-long Washington Post examination reveals that this erosion in life spans is deeper and broader than widely recognized, afflicting a far-reaching swath of the United States.

While opioids and gun violence have rightly seized the public’s attention, stealing hundreds of thousands of lives, chronic diseases are the greatest threat, killing far more people between 35 and 64 every year, The Post’s analysis of mortality data found.

Heart disease and cancer remained, even at the height of the pandemic, the leading causes of death for people 35 to 64. And many other conditions — private tragedies that unfold in tens of millions of U.S. households — have become more common, including diabetes and liver disease. These chronic ailments are the primary reason American life expectancy has been poor compared with other nations.

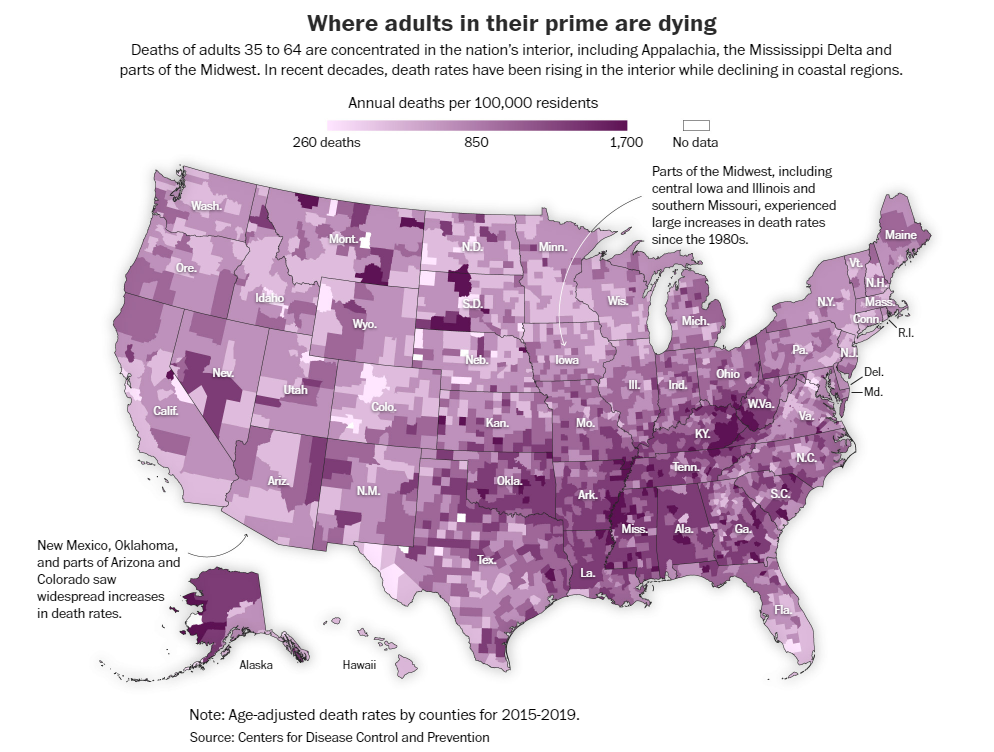

Sickness and death are scarring entire communities in much of the country. The geographical footprint of early death is vast: In a quarter of the nation’s counties, mostly in the South and Midwest, working-age people are dying at a higher rate than 40 years ago, The Post found. The trail of death is so prevalent that a person could go from Virginia to Louisiana, and then up to Kansas, by traveling entirely within counties where death rates are higher than they were when Jimmy Carter was president.

This phenomenon is exacerbated by the country’s economic, political and racial divides. America is increasingly a country of haves and have-nots, measured not just by bank accounts and property values but also by vital signs and grave markers. Dying prematurely, The Post found, has become the most telling measure of the nation’s growing inequality.

The mortality crisis did not flare overnight. It has developed over decades, with early deaths an extreme manifestation of an underlying deterioration of health and a failure of the health system to respond. Covid highlighted this for all the world to see: It killed far more people per capita in the United States than in any other wealthy nation.

Chronic conditions thrive in a sink-or-swim culture, with the U.S. government spending far less than peer countries on preventive medicine and social welfare generally. Breakthroughs in technology, medicine and nutrition that should be boosting average life spans have instead been overwhelmed by poverty, racism, distrust of the medical system, fracturing of social networks and unhealthy diets built around highly processed food, researchers told The Post.

The calamity of chronic disease is a “not-so-silent pandemic,” said Marcella Nunez-Smith, a professor of medicine, public health and management at Yale University. “That is fundamentally a threat to our society.” But chronic diseases, she said, don’t spark the sense of urgency among national leaders and the public that a novel virus did.

America’s medical system is unsurpassed when it comes to treating the most desperately sick people, said William Cooke, a doctor who tends to patients in the town of Austin, Ind. “But growing healthy people to begin with, we’re the worst in the world,” he said. “If we came in last in the next Olympics, imagine what we would do.”

The Post interviewed scores of clinicians, patients and researchers, and analyzed county-level death records from the past five decades. The data analysis concentrated on people 35 to 64 because these ages have the greatest number of excess deaths compared with peer nations.

What emerges is a dismaying picture of a complicated, often bewildering health system that is overmatched by the nation’s burden of disease:

“The big-ticket items are cardiovascular diseases and cancers,” said Arline T. Geronimus, a University of Michigan professor who studies population health equity. “But people always instead go to homicide, opioid addiction, HIV.”

Behind all the mortality statistics are the personal stories of loss, grief, hope. And anger. They are the stories of chronic illness in America and the devastating toll it exacts on millions of people — people like Bonnie Jean Holloway.

For years, Holloway rose at 3 a.m. to go to her waitress job at a small restaurant in Louisville that opened at 4 and catered to early-shift workers. Later, Holloway worked at a Bob Evans restaurant right off Interstate 65 in Clarksville, Ind. She often worked a double shift, deep into the evening. She was one of those waitresses who becomes a fixture, year after year.

Those years were not kind to Holloway’s health.

She never went to the doctor, not counting the six times she delivered a baby, according to her eldest daughter, Desirae Holloway. She was covered by Medicaid, but for many years, didn’t have a primary care doctor.

She developed rheumatoid arthritis, a severe autoimmune disease. “Her hands were twisted,” recalled friend and fellow waitress Dolly Duvall, who has worked at Bob Evans for 41 years. “Some days, she had to call in sick because she couldn’t get herself walking.”

The turning point came a little more than a decade ago when Holloway dropped a tray full of water glasses. She went home and wept. She knew she was done.

Her 50s became a trial, beset with multiple ailments, consistent with what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found — that people with chronic diseases often have them in bunches. She was diagnosed with emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — known as COPD — and could not go anywhere without her canister of oxygen.

Her family found the medical system difficult to trust. Medicines didn’t work or had terrible side effects. Drugs prescribed for Holloway’s autoimmune disease seemed to make her vulnerable to infections. She would catch whatever bug her grandkids caught. She developed a fungal infection in her lungs.

Tobacco looms large in this sad story. One of the signal successes of public health in the past half-century has been the drop in smoking rates and associated declines in lung cancer. But roughly 1 in 7 middle-aged Americans still smokes, according to the CDC. Kentucky has a deep cultural and economic connection to tobacco. The state’s smoking rates are the second-highest in the nation, trailing only West Virginia. Holloway began smoking at 12, Desirae said. And for a long time, restaurants still had a smoking section right next to the nonsmoking section.

Oct. 3 at 6:00 a.m.

The United States is failing at a fundamental mission — keeping people alive.

After decades of progress, life expectancy — long regarded as a singular benchmark of a nation’s success — peaked in 2014 at 78.9 years, then drifted downward even before the coronavirus pandemic. Among wealthy nations, the United States in recent decades went from the middle of the pack to being an outlier. And it continues to fall further and further behind.

A year-long Washington Post examination reveals that this erosion in life spans is deeper and broader than widely recognized, afflicting a far-reaching swath of the United States.

While opioids and gun violence have rightly seized the public’s attention, stealing hundreds of thousands of lives, chronic diseases are the greatest threat, killing far more people between 35 and 64 every year, The Post’s analysis of mortality data found.

Heart disease and cancer remained, even at the height of the pandemic, the leading causes of death for people 35 to 64. And many other conditions — private tragedies that unfold in tens of millions of U.S. households — have become more common, including diabetes and liver disease. These chronic ailments are the primary reason American life expectancy has been poor compared with other nations.

Sickness and death are scarring entire communities in much of the country. The geographical footprint of early death is vast: In a quarter of the nation’s counties, mostly in the South and Midwest, working-age people are dying at a higher rate than 40 years ago, The Post found. The trail of death is so prevalent that a person could go from Virginia to Louisiana, and then up to Kansas, by traveling entirely within counties where death rates are higher than they were when Jimmy Carter was president.

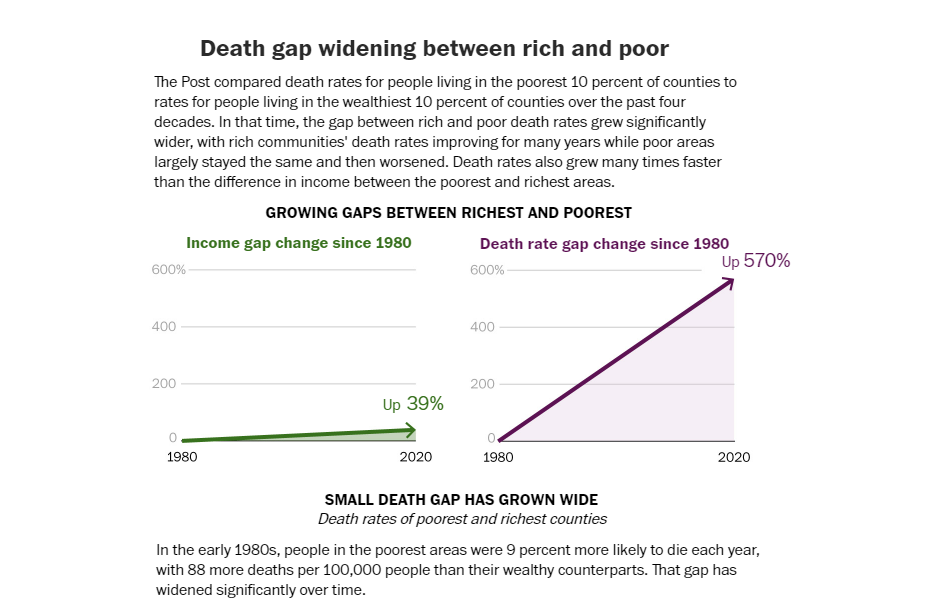

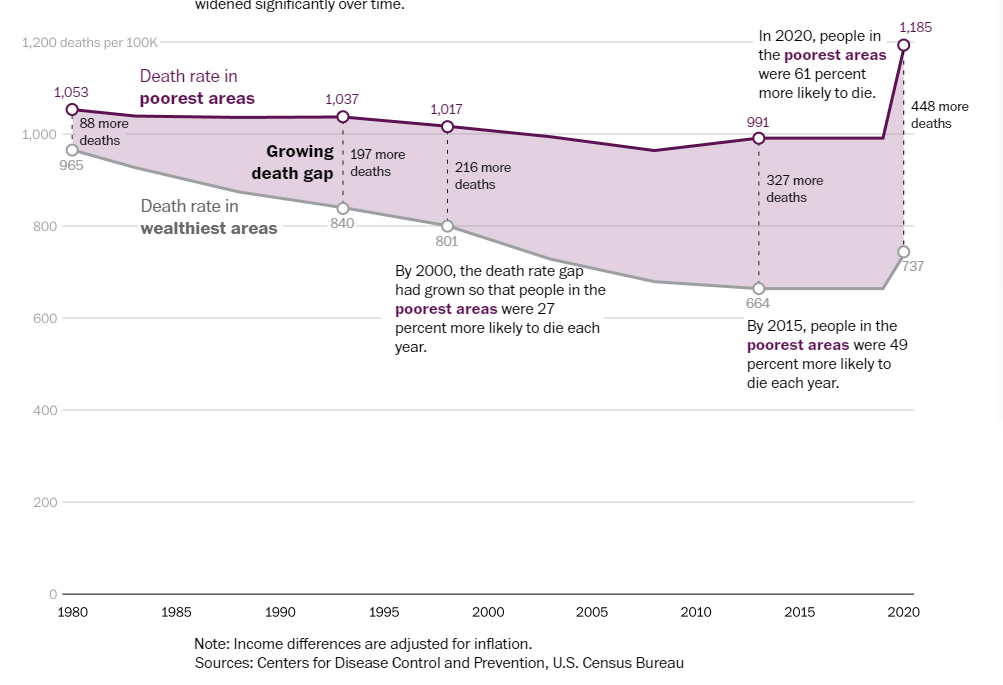

This phenomenon is exacerbated by the country’s economic, political and racial divides. America is increasingly a country of haves and have-nots, measured not just by bank accounts and property values but also by vital signs and grave markers. Dying prematurely, The Post found, has become the most telling measure of the nation’s growing inequality.

The mortality crisis did not flare overnight. It has developed over decades, with early deaths an extreme manifestation of an underlying deterioration of health and a failure of the health system to respond. Covid highlighted this for all the world to see: It killed far more people per capita in the United States than in any other wealthy nation.

Chronic conditions thrive in a sink-or-swim culture, with the U.S. government spending far less than peer countries on preventive medicine and social welfare generally. Breakthroughs in technology, medicine and nutrition that should be boosting average life spans have instead been overwhelmed by poverty, racism, distrust of the medical system, fracturing of social networks and unhealthy diets built around highly processed food, researchers told The Post.

The calamity of chronic disease is a “not-so-silent pandemic,” said Marcella Nunez-Smith, a professor of medicine, public health and management at Yale University. “That is fundamentally a threat to our society.” But chronic diseases, she said, don’t spark the sense of urgency among national leaders and the public that a novel virus did.

America’s medical system is unsurpassed when it comes to treating the most desperately sick people, said William Cooke, a doctor who tends to patients in the town of Austin, Ind. “But growing healthy people to begin with, we’re the worst in the world,” he said. “If we came in last in the next Olympics, imagine what we would do.”

The Post interviewed scores of clinicians, patients and researchers, and analyzed county-level death records from the past five decades. The data analysis concentrated on people 35 to 64 because these ages have the greatest number of excess deaths compared with peer nations.

What emerges is a dismaying picture of a complicated, often bewildering health system that is overmatched by the nation’s burden of disease:

- Chronic illnesses, which often sicken people in middle age after the protective vitality of youth has ebbed, erase more than twice as many years of life among people younger than 65 as all the overdoses, homicides, suicides and car accidents combined, The Post found.

- The best barometer of rising inequality in America is no longer income. It is life itself. Wealth inequality in America is growing, but The Post found that the death gap — the difference in life expectancy between affluent and impoverished communities — has been widening many times faster. In the early 1980s, people in the poorest communities were 9 percent more likely to die each year, but the gap grew to 49 percent in the past decade and widened to 61 percent when covid struck.

- Life spans in the richest communities in America have kept inching upward, but lag far behind comparable areas in Canada, France and Japan, and the gap is widening. The same divergence is seen at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder: People living in the poorest areas of America have far lower life expectancy than people in the poorest areas of the countries reviewed.

- Forty years ago, small towns and rural regions were healthier for adults in the prime of life. The reverse is now true. Urban death rates have declined sharply, while rates outside the country’s largest metro areas flattened and then rose. Just before the pandemic, adults 35 to 64 in the most rural areas were 45 percent more likely to die each year than people in the largest urban centers.

“The big-ticket items are cardiovascular diseases and cancers,” said Arline T. Geronimus, a University of Michigan professor who studies population health equity. “But people always instead go to homicide, opioid addiction, HIV.”

Behind all the mortality statistics are the personal stories of loss, grief, hope. And anger. They are the stories of chronic illness in America and the devastating toll it exacts on millions of people — people like Bonnie Jean Holloway.

For years, Holloway rose at 3 a.m. to go to her waitress job at a small restaurant in Louisville that opened at 4 and catered to early-shift workers. Later, Holloway worked at a Bob Evans restaurant right off Interstate 65 in Clarksville, Ind. She often worked a double shift, deep into the evening. She was one of those waitresses who becomes a fixture, year after year.

Those years were not kind to Holloway’s health.

She never went to the doctor, not counting the six times she delivered a baby, according to her eldest daughter, Desirae Holloway. She was covered by Medicaid, but for many years, didn’t have a primary care doctor.

She developed rheumatoid arthritis, a severe autoimmune disease. “Her hands were twisted,” recalled friend and fellow waitress Dolly Duvall, who has worked at Bob Evans for 41 years. “Some days, she had to call in sick because she couldn’t get herself walking.”

The turning point came a little more than a decade ago when Holloway dropped a tray full of water glasses. She went home and wept. She knew she was done.

Her 50s became a trial, beset with multiple ailments, consistent with what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found — that people with chronic diseases often have them in bunches. She was diagnosed with emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — known as COPD — and could not go anywhere without her canister of oxygen.

Her family found the medical system difficult to trust. Medicines didn’t work or had terrible side effects. Drugs prescribed for Holloway’s autoimmune disease seemed to make her vulnerable to infections. She would catch whatever bug her grandkids caught. She developed a fungal infection in her lungs.

Tobacco looms large in this sad story. One of the signal successes of public health in the past half-century has been the drop in smoking rates and associated declines in lung cancer. But roughly 1 in 7 middle-aged Americans still smokes, according to the CDC. Kentucky has a deep cultural and economic connection to tobacco. The state’s smoking rates are the second-highest in the nation, trailing only West Virginia. Holloway began smoking at 12, Desirae said. And for a long time, restaurants still had a smoking section right next to the nonsmoking section.